Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: Abbreviated antiplatelet therapy (APT) can reduce bleeding without increasing ischaemic harm in high bleeding risk (HBR) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The impact of chronic kidney disease (CKD) on the safety and effectiveness of abbreviated APT remains unknown.

Aims: We aimed to investigate the comparative effectiveness of abbreviated (1 month) versus standard (≥3 months) APT in HBR patients with and without CKD.

Methods: This was a prespecified analysis from the MASTER DAPT trial, which randomised 4,579 HBR patients (1,428 [31%] with CKD) to abbreviated or standard APT. CKD was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Co-primary outcomes were net adverse clinical events (NACE; a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction [MI], stroke, and major bleeding), major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (MACCE; all-cause death, MI and stroke), and Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 2, 3, or 5 bleeding at 11 months.

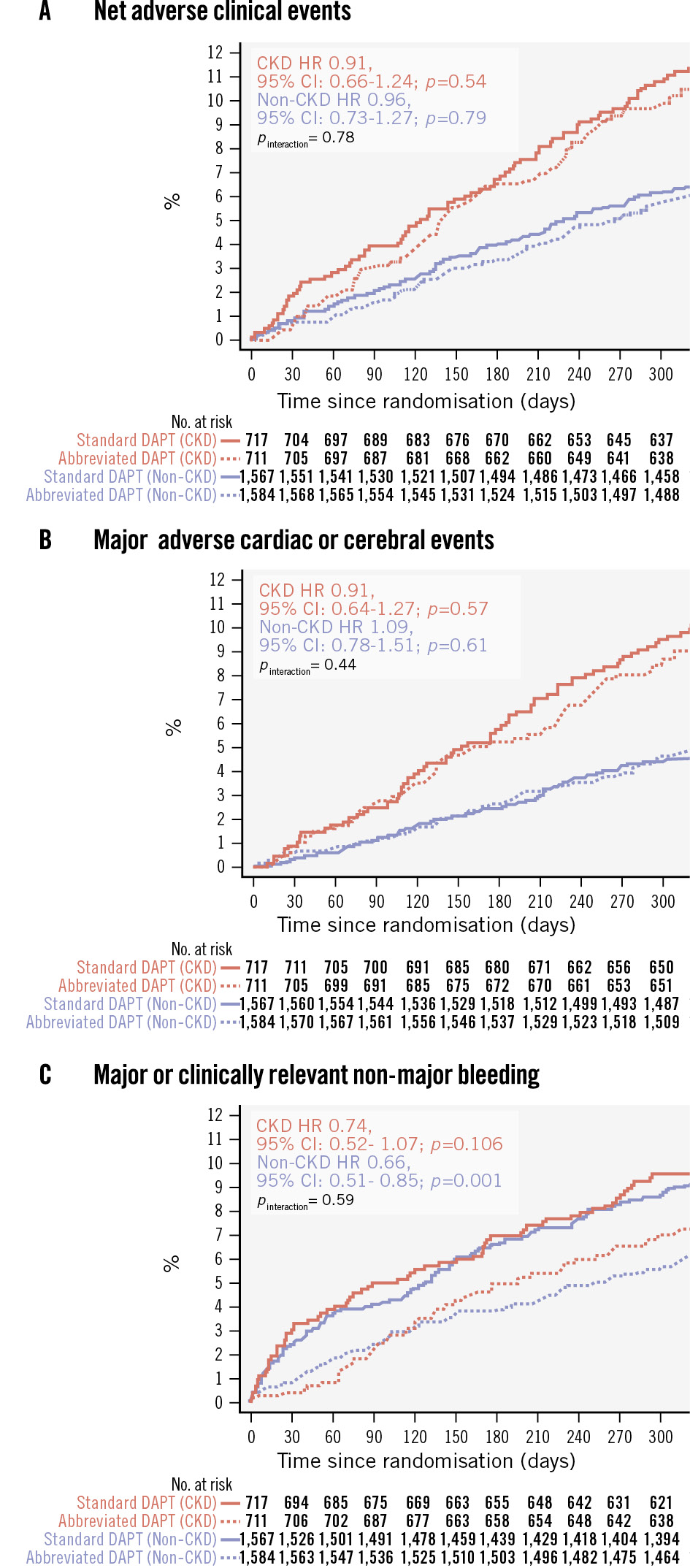

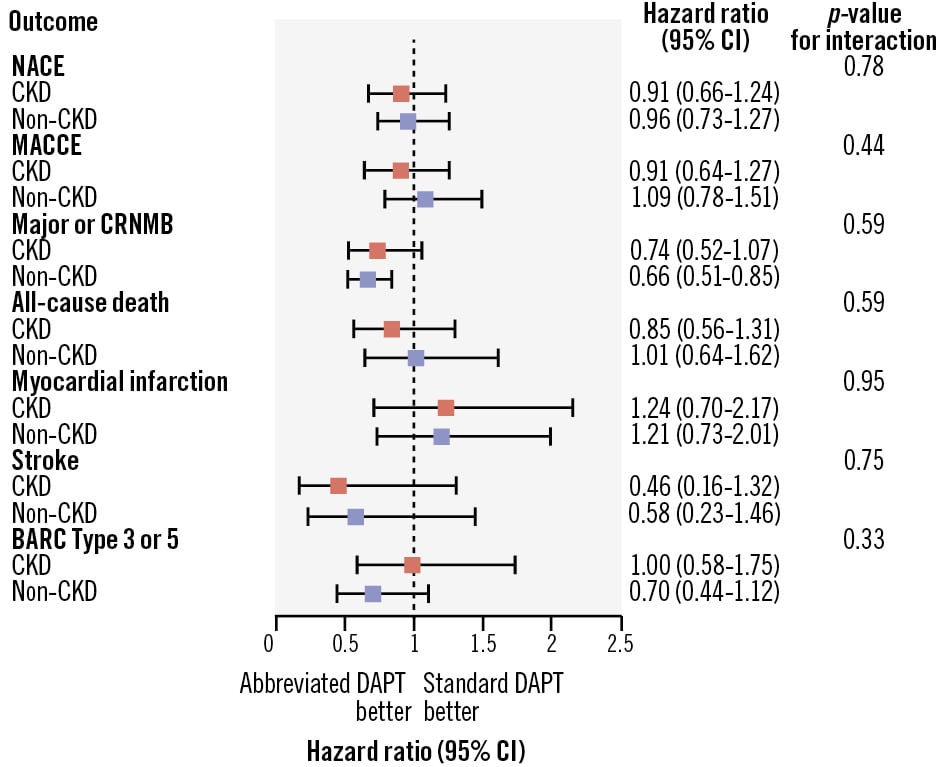

Results: NACE did not significantly differ with abbreviated and standard APT among CKD patients (hazard ratio [HR] 0.91, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.66-1.24) and non-CKD patients (HR 0.96, 95% CI: 0.73-1.27; pinteraction=0.78). Similarly, MACCE did not differ in CKD patients (HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.64-1.27) and non-CKD patients (HR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.78-1.51; pinteraction=0.45). Abbreviated APT was associated with consistently lower BARC 2, 3, or 5 bleeding in both patients with CKD (HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.52-1.07) and without it (HR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51-0.85; pinteraction=0.59).

Conclusions: Abbreviated APT was associated with similar NACE and MACCE rates and reduced bleeding compared with standard APT in HBR patients undergoing PCI, regardless of the presence or absence of CKD. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03023020)

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a highly prevalent clinical condition, affecting more than 850 million individuals worldwide with a global median prevalence of 9.5%12. The burden of renal dysfunction is even more prevalent among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)3. Accumulating evidence suggests that CKD patients undergoing PCI face increased risks of both ischaemic and bleeding complications45. This “double hazard” may be explained by altered platelet function and coagulation pathways6, reduced responsiveness to antiplatelet agents7, and a greater burden of comorbidities in this population5. Furthermore, CKD is associated with more advanced and complex CAD, including a higher prevalence of multivessel disease, left main involvement, chronic total occlusions, extensive calcifications, and increased plaque burden89.

Patients undergoing PCI typically require a combination of aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, commonly referred to as dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), to mitigate the risk of ischaemic recurrences, including stent thrombosis (ST)1011. However, this ischaemic protection offered by DAPT must be balanced against an elevated risk of bleeding, especially in patients at high bleeding risk (HBR)12. As such, the optimal DAPT duration after PCI for the prevention of ischaemic and bleeding complications in HBR-CKD patients remains a clinical conundrum.

The Management of High Bleeding Risk Patients Post Bioresorbable Polymer Coated Stent Implantation With an Abbreviated Versus Prolonged DAPT Regimen (MASTER DAPT) study demonstrated that abbreviated (1-month) DAPT was non-inferior to treatment continuation for at least 2 additional months for net and major adverse clinical events and was associated with reduced major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNMB) in HBR patients treated with a biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stent131415. In this prespecified analysis of MASTER DAPT, we sought to investigate whether the treatment effects of abbreviated versus standard antiplatelet therapy (APT) differ according to the presence of CKD in this HBR population.

Methods

Study design

This is a prespecified analysis of MASTER DAPT (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03023020), an investigator-initiated, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial with sequential superiority testing, enrolling an unselected patient population at HBR following implantation of a biodegradable-polymer-coated Ultimaster sirolimus-eluting stent (Terumo). Study methodology and the primary results of MASTER DAPT have been previously reported1314151617. The trial was approved by the institutional review board at each participating site, and all patients gave written informed consent. An independent data safety monitoring board regularly reviewed the conduct of the trial and patient safety. Study organisation and participating sites are reported in Supplementary Appendix 1, along with a complete list of the MASTER DAPT investigators.

Study population

Patients at HBR were deemed eligible for trial participation if they underwent treatment of all coronary lesions requiring revascularisation with an Ultimaster stent for acute or chronic coronary syndromes and remained event-free (including a new ACS, symptomatic restenosis, ST, stroke, or any revascularisation resulting in the prolonged use of DAPT) during the first month after index PCI. Patients were considered at HBR if at least one of the following criteria applied: oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy for at least 12 months, recent (<12 months) non-access site bleeding episode(s) that required medical attention, previous bleeding episode(s) that required hospitalisation if the underlying cause had not been definitively treated, age ≥75 years, systemic conditions associated with an increased bleeding risk (e.g., haematological or coagulation disorders), documented anaemia, need for chronic treatment with steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, malignancy (other than skin), stroke at any time or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) in the previous 6 months, or PREdicting bleeding Complications In patients undergoing Stent implantation and subsequent DAPT (PRECISE-DAPT) score ≥2518.

Key exclusion criteria were the implantation of any stent other than the Ultimaster stent within the previous 6 months, a bioresorbable scaffold at any time before the index procedure, or stenting for in-stent restenosis or ST. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Renal function assessment

Renal function was evaluated using the most recent value of serum creatinine after the index PCI prior to hospital discharge. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation. Chronic kidney disease was defined as an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. For subgroup analysis, CKD severity was further stratified into mild-to-moderate CKD (eGFR ≥30 but <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and severe CKD (<30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Randomisation and follow-up

Patients were centrally randomised (1:1 ratio) to an open-label abbreviated or standard APT regimen 30 to 44 days after the index procedure. Randomisation was concealed using a web-based system; randomisation sequences were computer-generated, blocked (with randomly selected block sizes of 2, 4, or 6), and were stratified by site, history of acute myocardial infarction (MI) within the past 12 months, and clinical indication for at least 12-month OAC.

Patients randomly allocated to the abbreviated treatment group immediately discontinued DAPT and continued single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) until study completion, except for those receiving OAC, who continued SAPT up to 6 months after the index procedure. Patients allocated to the standard treatment group continued DAPT for at least 5 additional months (i.e., 6 months after the index procedure) or, for those receiving OAC, for at least 2 additional months (i.e., 3 months after the index procedure) followed by SAPT. Follow-up visits took place at 60 days, 150 days, and 335 days (all with a ±14-day window) after randomisation.

Outcomes

The three ranked co-primary outcomes were net adverse clinical events (NACE; the composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or major bleeding), major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (MACCE; the composite of death from any cause, MI, or stroke), and major or CRNMB (the composite of Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] Type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding) at 11 months after randomisation (12-month follow-up).

Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the three co-primary outcomes, cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular death, cerebrovascular accidents (CVA; the composite of stroke and TIA), definite or probable ST, and all BARC bleeding events. All events were adjudicated by an independent adjudication committee that was unaware of the treatment allocations. All data were stored at a central database (Department of Clinical Research, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland).

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Outcomes were assessed separately for patients with or without CKD, by calculating hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For patients with a primary outcome, the time to event was calculated as the difference between the date of occurrence of the outcome event and the date of randomisation, plus 1 day. For patients with incomplete clinical follow-up, the time to censoring was defined as the difference between the dates of the last known clinical status and randomisation, plus 1 day. The Com-Nougue method was used to analyse the time to event, with day 0 defined as the date of randomisation at the 1-month visit and the analysis extending up to 335 days thereafter. Kaplan-Meier calculations included all (first) adjudicated outcome events that occurred between randomisation and 335 days thereafter according to the randomised treatment assignment, irrespective of the DAPT regimen received at the time of the outcome event. HRs and 95% CIs were generated for primary and secondary outcomes with the use of Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, with censoring at the end of the study and at the time of death. P-values for testing the homogeneity of the HR in subgroups of patients (including those with or without a concomitant indication for OAC and by CKD severity) were derived from Cox proportional hazards models, with the interaction term for treatment group (abbreviated vs standard) and CKD (yes vs no) tested using one degree of freedom. The continuous relation between eGFR used as continuous variable with NACE, MACCE, and major or CRNMB was assessed using spline functions. The analyses were carried out using Stata/SE 16.0 (StataCorp).

Results

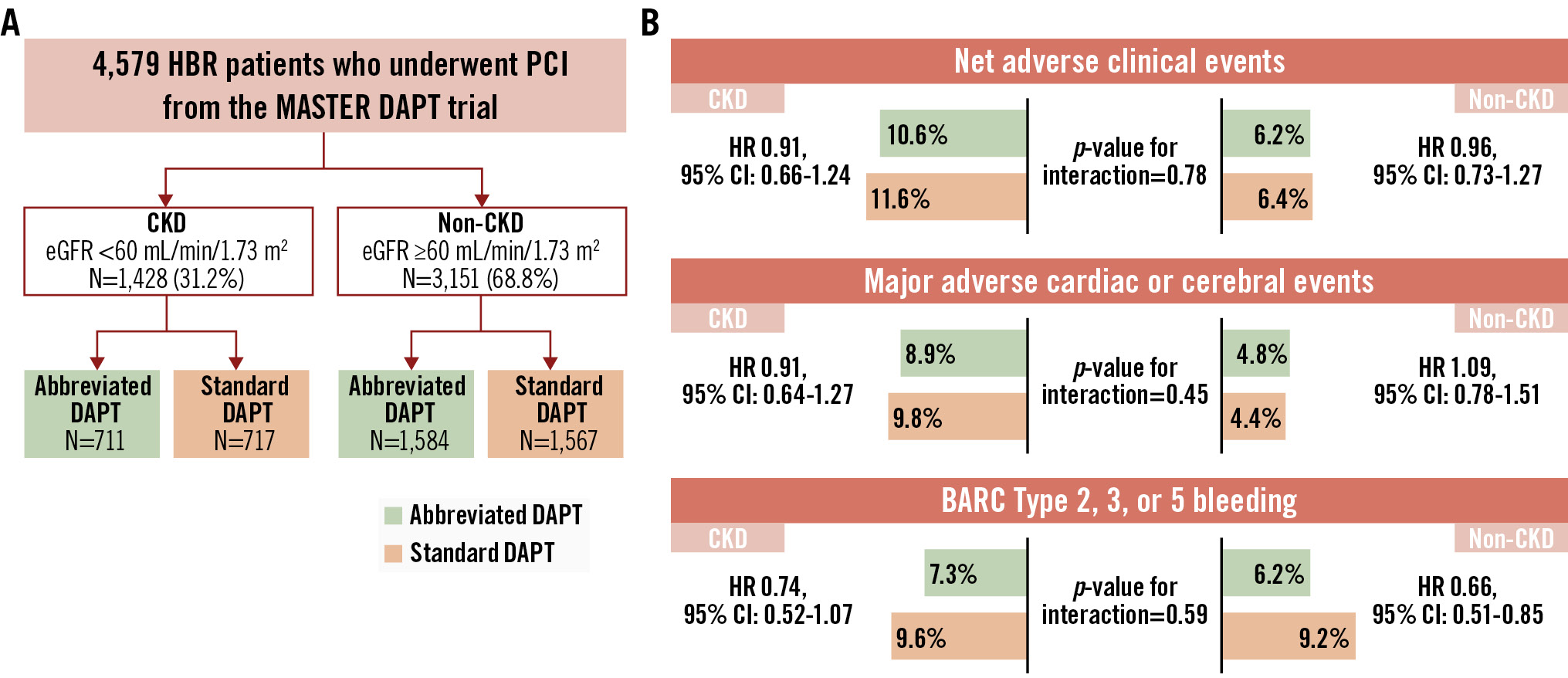

Among the 4,579 patients enrolled in the MASTER DAPT trial, 1,428 patients (31%) had CKD. Randomisation occurred at a median of 34 days post-PCI (interquartile range: 32 to 39 days) to either an abbreviated (n=2,295 [CKD: n=711; non-CKD: n=1,584]) or a standard (n=2,284 [CKD: n=717; non-CKD: n=1,567]) APT. The composition of DAPT and type of SAPT did not differ between patients with and without CKD (Supplementary Table 1).

Baseline and procedural characteristics

Patients with CKD were older, more often female, and had a higher cardiovascular risk burden, including arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prior MI or coronary revascularisation, compared with non-CKD patients (Supplementary Table 2). CKD patients had a lower left ventricular ejection fraction (51.2% vs 54.1%; p<0.001), more frequently had haematological or coagulation disorders (20.2% vs 9.2%; p<0.001), and had higher PRECISE DAPT scores (34.24±10.13 vs 23.37±9.59; p<0.001) than non-CKD patients (Supplementary Table 2). The mean creatinine clearance was 47.2±16.1 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 81.6±18.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 in CKD and non-CKD patients (p<0.001), respectively. Non-ST-segment elevation ACS was more prevalent in CKD patients than in non-CKD patients (30.5% vs 22.8%; p<0.001), while stable angina was less common (36.3% vs 42.2%; p<0.001).

Supplementary Table 3 shows angiographic and procedural characteristics in CKD and non-CKD patients. CKD patients underwent PCI more frequently via transfemoral access and had a higher prevalence of treated vessels or complex lesions (type B2/C, left main, or lesion requiring rotational atherectomy) than non-CKD patients. Baseline and procedural characteristics according to CKD and the randomly allocated APT were well balanced between the groups except for a lower prevalence of prior CVA, radial access, and multivessel PCI in non-CKD patients treated with abbreviated compared with standard APT (Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Table 5).

Clinical outcomes by CKD

At 11-month follow-up (Table 1), the incidence of NACE was higher in CKD patients than in non-CKD patients (11.10% vs 6.25%; HR 1.82, 95% CI: 1.48-2.24; p<0.001). The rate of MACCE was also higher in CKD patients compared with non-CKD patients (9.34% vs 4.56%; HR 2.10, 95% CI: 1.66-2.66; p<0.001), whereas major or CRNMB occurred in 119 of 1,428 CKD patients (8.48%) and in 240 of 3,151 non-CKD patients (7.70%; HR 1.10, 95% CI: 0.89-1.38; p=0.375). The rates of death (either cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular), CVA, and MI were higher in CKD patients than in those without CKD. BARC Type 3 or 5 bleeding occurred in 50 of 1,428 CKD patients (3.58%) and in 72 of 3,151 non-CKD patients (2.31%; HR 1.55, 95% CI: 1.08-2.23; p=0.017).

Table 1. Clinical outcomes at 11 months after randomisation in HBR patients with versus without CKD.

| CKD (n=1,428) | Non-CKD (n=3,151) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NACE | 158 (11.10) | 196 (6.25) | 1.82 (1.48-2.24) | <0.001 |

| MACCE | 133 (9.34) | 143 (4.56) | 2.10 (1.66-2.66) | <0.001 |

| Major or CRNMB | 119 (8.48) | 240 (7.70) | 1.10 (0.89-1.38) | 0.375 |

| Death | 85 (5.97) | 71 (2.27) | 2.68 (1.96-3.68) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 43 (3.06) | 38 (1.22) | 2.54 (1.64-3.92) | <0.001 |

| Non-cardiovascular death | 29 (2.09) | 28 (0.90) | 2.32 (1.38-3.91) | 0.001 |

| Undetermined death | 13 (0.93) | 5 (0.16) | 5.83 (2.08-16.34) | 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 23 (1.65) | 26 (0.84) | 1.99 (1.13-3.48) | 0.017 |

| Stroke* | 16 (1.15) | 19 (0.61) | 1.89 (0.97-3.67) | 0.061 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 13 (0.93) | 16 (0.52) | 1.82 (0.87-3.78) | 0.109 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 4 (0.29) | 2 (0.06) | 4.51 (0.83-24.62) | 0.082 |

| TIA | 7 (0.51) | 7 (0.23) | 2.25 (0.79-6.40) | 0.130 |

| Myocardial infarction | 49 (3.52) | 60 (1.93) | 1.84 (1.26-2.68) | 0.002 |

| Definite or probable ST | 9 (0.65) | 14 (0.45) | 1.44 (0.62-3.32) | 0.397 |

| Definite ST | 4 (0.29) | 14 (0.45) | 0.64 (0.21-1.94) | 0.428 |

| Probable ST | 5 (0.36) | 0 (0) | 24.27 (1.34-438.62) | 0.003 |

| Bleeding (BARC classification) | ||||

| BARC Type 1 | 51 (3.64) | 123 (3.95) | 0.92 (0.67-1.28) | 0.627 |

| BARC Type 2 | 74 (5.29) | 180 (5.78) | 0.91 (0.70-1.20) | 0.517 |

| BARC Type 3 | 44 (3.15) | 68 (2.19) | 1.45 (0.99-2.11) | 0.057 |

| BARC Type 3a | 26 (1.86) | 30 (0.96) | 1.94 (1.15-3.28) | 0.014 |

| BARC Type 3b | 14 (1.01) | 27 (0.87) | 1.16 (0.61-2.21) | 0.656 |

| BARC Type 3c | 5 (0.36) | 11 (0.35) | 1.02 (0.35-2.92) | 0.978 |

| BARC Type 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| BARC Type 5 | 6 (0.44) | 4 (0.13) | 3.37 (0.95-11.95) | 0.060 |

| BARC Type 5a | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.03) | 2.24 (0.14-35.80) | 0.569 |

| BARC Type 5b | 5 (0.37) | 3 (0.10) | 3.75 (0.90-15.70) | 0.070 |

| BARC Type 3 or 5 | 50 (3.58) | 72 (2.31) | 1.55 (1.08-2.23) | 0.017 |

| Data are given as n (%). No. of first events of each type (Kaplan-Meier failure %). Hazard ratio (95% CI) from Cox time-to-first event analyses in the ITT population. Continuity corrected risk ratios (95% CI) in case of zero events with Fisher's exact test p-value. Interaction p-value testing for the modifying effect of CKD (yes or no) on the hazard ratio scale. *Includes undetermined strokes. Event counts for stroke subtypes reflect all the subtypes separately (e.g., no hierarchical counting was applied). BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CRNMB: clinically relevant non-major bleeding; HBR: high bleeding risk; HR: hazard ratio; ITT: intention-to-treat; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; NACE: net adverse clinical events; ST: stent thrombosis; TIA: transient ischaemic attack | ||||

Clinical outcomes by CKD and randomly allocated antiplatelet regimens

Clinical outcomes at 11 months in CKD and non-CKD patients stratified by APT are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. NACE did not differ between abbreviated and standard APT among CKD patients (75 [10.60%] vs 83 [11.59%]; HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.66-1.24; p=0.540) and non-CKD patients (97 [6.15%] vs 99 [6.35%]; HR 0.96, 95% CI: 0.73-1.27; p=0.792), with no significant heterogeneity of the treatment effect at interaction testing (pinteraction=0.780) (Supplementary Table 6). Similarly, MACCE did not differ with abbreviated and standard APT among CKD (63 [8.90%] vs 70 [9.78%]; HR 0.91, 95% CI: 0.64-1.27; p=0.570) and non-CKD patients (75 [4.76%] vs 68 [4.37%]; HR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.78-1.51; p=0.610), with no heterogeneity (pinteraction=0.445) (Supplementary Table 6). Major or CRNMB was consistently reduced with abbreviated versus standard APT in CKD patients (51 [7.33%] vs 68 [9.63%]; HR 0.74, 95% CI: 0.52-1.07; p=0.106) and non-CKD patients (97 [6.19%] vs 143 [9.23%]; HR 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51-0.85; p=0.001; pinteraction=0.590) (Supplementary Table 6). There was no evidence of heterogeneity of the treatment effects (all pinteraction>0.1) by CKD for any of the individual components of the co-primary endpoints or other secondary endpoints (Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Figure 1). Major or CRNMB reduction with abbreviated DAPT was mainly driven by lower rates of BARC Type 2 bleeding, both in CKD (HR 0.68, 95% CI: 0.43-1.08; p=0.100; risk difference −1.95) and non-CKD patients (HR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.48-0.87; p=0.004; risk difference −2.38; pinteraction=0.880) (Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves showing the three co-primary outcomes. Kaplan-Meier curves for NACE (A), MACCE (B) and major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (C). CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; HR: hazard ratio; MACCE: major adverse cardiac or cerebral events; NACE: net adverse clinical events

Figure 2. Main outcomes of abbreviated versus standard antiplatelet therapy in CKD and non-CKD patients. Abbreviated and standard DAPT were compared based on CKD status, with hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the three co-primary outcomes and their components (all-cause death, myocardial infarction, stroke, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] Type 3 or 5 bleeding). CKD: chronic kidney disease; CRNMB: clinically relevant non-major bleeding; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; MACCE: major adverse cardiac and cerebral events; NACE: net adverse clinical events

Outcomes in CKD and non-CKD patients with or without a clinical indication for OAC

Among patients with an indication for OAC (Supplementary Table 7), NACE, MACCE and major or CRNMB were similar between abbreviated and standard APT regardless of the presence or absence of CKD.

Among patients without an indication for OAC (Supplementary Table 8), major or CRNMB was significantly reduced with abbreviated APT in both CKD (HR 0.61, 95% CI: 0.36-1.04; p=0.072) and non-CKD patients (HR 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36-0.76; p=0.001), with no interaction (p=0.653).

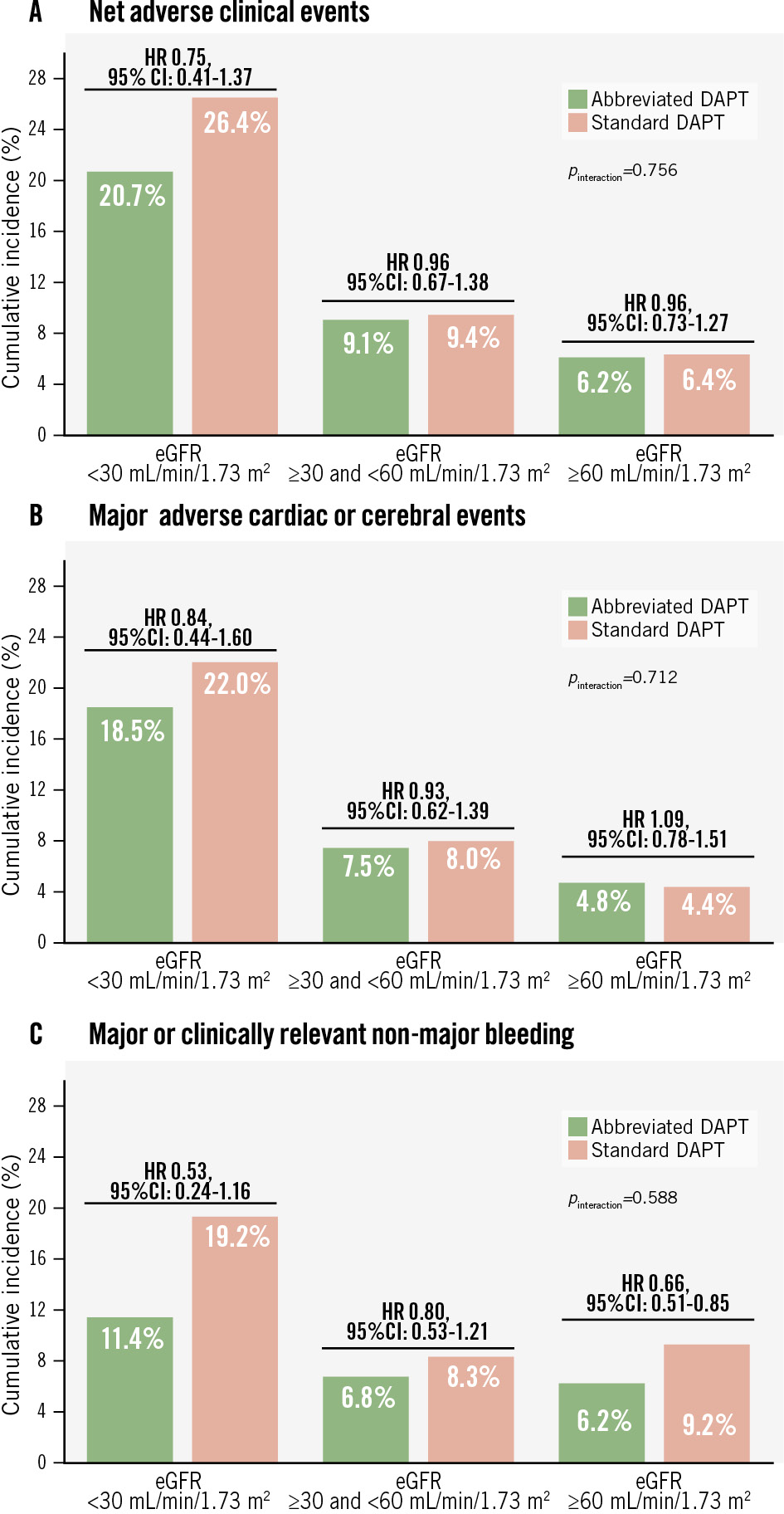

Additional post hoc analyses

Of the 1,428 CKD patients, 1,245 (87.2%) had mild-to-moderate CKD (eGFR 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2), while 183 (12.8%) had severe CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2). Event rates increased progressively with worsening renal function (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 9). No significant heterogeneity of the treatment effect between CKD severity and the randomly allocated APT regimen for any of the three co-primary endpoints was observed (pinteraction>0.1) (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 9). However, the absolute risk difference in major or CRNMB associated with abbreviated APT was greater in patients with severe CKD (−8.05%) compared with mild-to-moderate CKD (−1.5%) and non-CKD (−3.04%) (Supplementary Table 9).

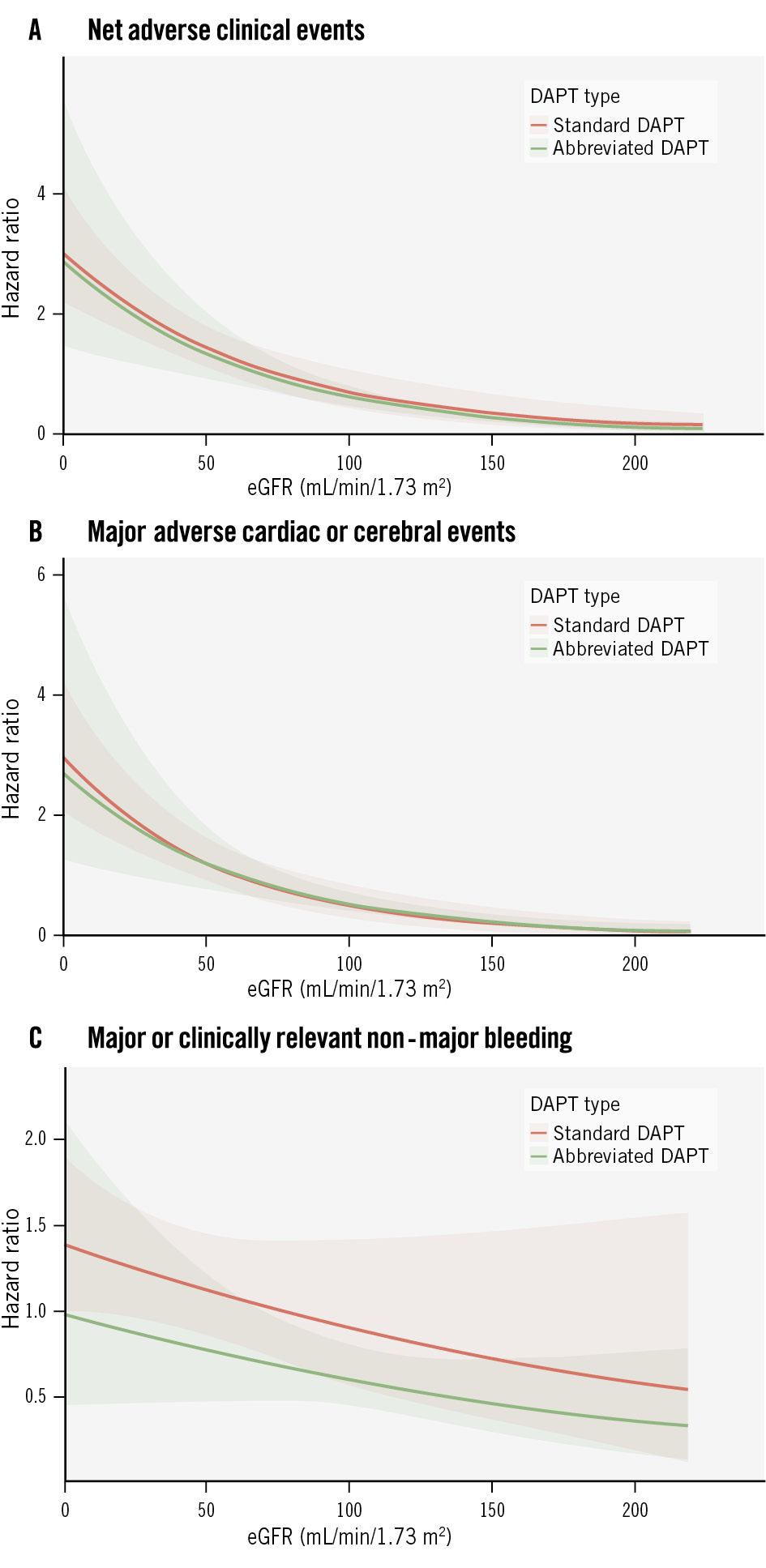

Figure 4 shows spline functions for NACE, MACCE, and major or CRNMB using eGFR as a continuous variable. The risks of NACE and MACCE did not significantly differ with abbreviated versus standard APT as eGFR decreased. However, the absolute risk reduction in major or CRNMB with abbreviated APT progressively increased as a function of renal impairment severity (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Interaction between CKD severity and antiplatelet therapy on the three co-primary efficacy outcomes. The x-axis shows the categories of the patients according to CKD severity, and the y-axis shows the event rates of the co-primary efficacy outcomes: net adverse clinical events (A), major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (B), and major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (C). CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR: hazard ratio

Figure 4. Spline functions of the three co-primary outcomes. Spline functions of net adverse clinical events (A), major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (B), and major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (C) in patients randomly allocated to abbreviated or standard DAPT according to eGFR. DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the largest analyses investigating the comparative effectiveness and safety of abbreviated versus standard APT in HBR patients with or without CKD undergoing PCI (Central illustration). The main findings from this prespecified analysis can be summarised as follows:

1. Patients with CKD experienced a 2-fold higher risk of net and major adverse cardiac or cerebral events at 1 year post-PCI, due to higher rates of death, MI, CVA, and major bleeding compared with patients without CKD.

2. There was no evidence of heterogeneity between CKD status and the effect of randomly allocated APT regimens on the three co-primary outcomes, suggesting that abbreviated APT was consistently associated with similar NACE and MACCE rates and lower major or CRNMB rates compared with standard APT, in both CKD and non-CKD patients.

3. Stepwise increases in both bleeding and ischaemic risks were observed with worsening renal function. The absolute and relative benefits of abbreviated APT were more pronounced in patients with severe CKD compared with mild-moderate dysfunction and non-CKD patients.

The observation of similar NACE and MACCE rates and a consistent reduction in bleeding events with abbreviated compared with standard APT, irrespective of CKD status, challenges the notion that patients with CKD require prolonged DAPT for ischaemic protection. Current guidelines provide no specific recommendations for DAPT duration after PCI based on renal function1920. Although CKD was not an inclusion criterion of the MASTER DAPT trial, renal dysfunction is considered a major (if severe) or minor (if moderate) criterion for HBR by the Academic Research Consortium21, and eGFR is one of the five items included in the PRECISE DAPT score18. Likewise, CKD is listed among the thrombotic risk enhancers according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, which recommend that a second antithrombotic agent in addition to aspirin should or may be considered in patients with and without complex CAD with a Class IIa and IIb recommendation, respectively1920. However, these recommendations apply to non-HBR patients.

At secondary endpoint analyses, we observed greater benefits in terms of absolute and relative risk reduction with abbreviated APT in patients with severely impaired renal function. Patients with severe CKD had significantly higher risks of adverse events compared with patients with moderate CKD or preserved renal function. In this high-risk subgroup, abbreviated APT was associated with a greater bleeding benefit without an incremental ischaemic risk compared with standard APT. Although the upper bound of the 95% CI slightly exceeded unity, likely due to the limited sample size, the results remain reassuring.

Our findings align with those from the XIENCE Short DAPT clinical programme encompassing data from three prospective single-arm studies, which included 3,286 HBR PCI patients (43.6% with CKD) treated with 1- or 3-month DAPT followed by aspirin monotherapy22. One- versus 3-month DAPT was associated with comparable rates of the composite primary endpoint of all-cause death or MI in CKD (adjusted HR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.60-1.22) and non-CKD patients (adjusted HR 1.15, 95% CI: 0.77-1.73; pinteraction=0.299). BARC Type 2 to 5 bleeding was consistently reduced with 1- compared with 3-month DAPT in CKD (HR 0.74, 95 CI: 0.52-1.04) and non-CKD patients (HR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.48-1.03), with no significant heterogeneity at interaction testing (pinteraction=0.462). Our results expand on these findings in a larger HBR cohort predominantly managed with P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy (clopidogrel in 53.9%, ticagrelor in 13.6%, prasugrel in 1.2%) rather than aspirin (28.8%).

Conversely, the Swedish Web-System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry showed that prolonged (>3 months) compared with 3-month DAPT was associated with lower risks of the composite endpoint of death, MI, or ischaemic stroke (adjusted HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.73-0.96) and net adverse events (HR 0.84, 95% CI: 0.78-0.91), with an enhanced magnitude of the treatment effects as renal function worsens23. However, prolonged DAPT was associated with a 31% relative increase in bleeding compared with 3-month DAPT23. The SWEDEHEART study was not randomised and exclusively included ACS patients without HBR features. The proportion of ACS patients was 50.8% in MASTER DAPT and 35.8% in the XIENCE Short DAPT clinical programme. In a post hoc analysis of the Harmonizing Optimal Strategy for Treatment of Coronary Artery Diseases Trial -Comparison of REDUCTION of PrasugrEl Dose and POLYmer TECHnology in ACS Patients (HOST REDUCE POLYTECH RCT) Trial, which randomised ACS patients to DAPT de-escalation (prasugrel 5 mg from 1 month onwards) versus conventional therapy with aspirin and prasugrel 10 mg for 12 months24, prasugrel de-escalation was associated with a greater bleeding benefit and similar ischaemic risk as renal function worsened24. These results suggest that patients with severe CKD may derive enhanced bleeding benefit without ischaemic harm from DAPT de-escalation.

In MASTER DAPT, patients underwent PCI with biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stents, which limits the generalisability of these findings to other stent platforms. However, while the majority of randomised trials provided evidence on stent type selection by comparing different stent platforms in HBR patients252627, MASTER DAPT is the only trial investigating the optimal duration of DAPT in patients who were selected specifically for HBR.

Although there are no dedicated trials for CKD patients, subgroup analyses of randomised clinical trials have also investigated the efficacy and safety of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy after 1 to 3 months of DAPT in CKD and non-CKD patients. In the GLOBAL LEADERS trial, which randomised 15,991 patients with chronic or ACS to 1-month DAPT (aspirin and ticagrelor) followed by 23-month ticagrelor monotherapy versus 12-month DAPT followed by aspirin alone28, no significant differences in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality or new Q-wave MI nor BARC Type 3 or 5 bleeding were observed28. A prespecified subgroup analysis showed no heterogeneity of the treatment effects between the randomly allocated APT and CKD status29. Ticagrelor-based monotherapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of BARC Type 3 or 5 bleeding as eGFR decreased29. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the overall negative trial outcome and the low prevalence of CKD (14% of the overall study population). Our results further extend these findings to a contemporary HBR population. In the Ticagrelor With Aspirin or Alone in High-Risk Patients after Coronary Intervention (TWILIGHT) trial, ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT was associated with a lower risk of BARC Type 2 to 5 bleeding and a similar risk of ischaemic events in CKD and non-CKD patients compared with ticagrelor plus aspirin30. In an individual patient data meta-analysis comprising 25,960 patients from 6 trials, ticagrelor monotherapy was non-inferior to 12-month DAPT for the composite primary endpoint of death, MI, or stroke (HR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.74-1.06; p for non-inferiority=0.004) and superior for major bleeding (HR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.36-0.62; p<0.001)31. Compared with 12-month DAPT, clopidogrel monotherapy was associated with lower bleeding (HR 0.49, 95% CI: 0.30-0.81; p=0.006) but failed to show non-inferiority for the composite primary ischaemic endpoint (HR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.01-1.87; p for non-inferiority>0.99). Subgroup analyses for the primary endpoint demonstrated consistent treatment effects in patients with and without CKD without significant heterogeneity at interaction testing (pinteraction=0.74 for ticagrelor; pinteraction=0.51 for clopidogrel).

Taken together, this body of evidence – including our current analysis – suggests that CKD, while a marker of elevated ischaemic risk, should not be the sole determinant for prolonging DAPT in HBR patients. Abbreviated APT strategies are supported and may be particularly favourable in patients with impaired renal function.

Central illustration. Abbreviated or standard antiplatelet therapy in high bleeding risk patients with and without CKD. A) Study design. (B) Study outcomes. BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; HBR: high bleeding risk; HR: hazard ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the MASTER DAPT trial was not powered for non-inferiority comparisons of NACE and MACCE with abbreviated versus standard APT in the CKD subgroup, and randomisation was not stratified by CKD. Thus, our findings should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating. Dedicated prospective studies are required to assess the risks and benefits of an abbreviated versus standard APT regimen in this patient population. Second, the trial included only patients who were free of ischaemic and bleeding events in the first month post-PCI using biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stents. Therefore, these findings may not apply to patients experiencing early adverse events, those at low bleeding risk, or those treated with other stent platforms. Third, in this analysis, CKD was based on a single post-PCI creatinine measurement without accounting for baseline values. Finally, patients with in-stent restenosis or ST were excluded, limiting generalisability to these populations.

Conclusions

In this prespecified analysis of the MASTER DAPT trial, abbreviated APT was associated with similar NACE and MACCE and reduced major or CRNMB compared with standard APT, regardless of renal function. In HBR patients with severe CKD undergoing biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting coronary stent implantation, abbreviated APT appears particularly beneficial, offering significant bleeding reduction without increased ischaemic harm. These findings support the consideration of a shortened APT regimen in HBR-CKD patients after PCI with biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stents.

Impact on daily practice

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) have higher risks of ischaemic and bleeding events than non-CKD subjects. The optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in CKD patients with concomitant high bleeding risk (HBR) features represents a clinical conundrum. In this prespecified analysis from the MASTER DAPT trial, an abbreviated DAPT duration was associated with comparable major and net adverse clinical events and consistently reduced bleeding, compared with treatment continuation, for at least two additional months, regardless of renal function. These findings support an abbreviated DAPT regimen in HBR-CKD patients after PCI with biodegradable-polymer sirolimus-eluting stents. Future studies should investigate the safety and efficacy of abbreviated DAPT in HBR patients with end-stage renal disease or those on dialysis treatment.

Funding

The study was sponsored by the European Cardiovascular Research Institute, a non-profit organisation, and received grant support from Terumo.

Conflict of interest statement

A. Landi declares that he has received consulting fees from Terumo, outside the submitted work. F. Mahfoud has been supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB TRR219, Project-ID 322900939), and Deutsche Herzstiftung; Saarland University has received scientific support from Ablative Solutions, Medtronic, and Recor Medical; up to May 2024, he received speaker honoraria/consulting fees from Ablative Solutions, AstraZeneca, Inari, Medtronic, Merck & Co, Novartis, Philips, and Recor Medical. D. Heg and K. Chalkou are employed by the Department of Clinical Research (DCR), University of Bern, which has a staff policy of not accepting honoraria or consultancy fees; however, the DCR is involved in the design, conduct, and analysis of clinical studies funded by not-for-profit and for-profit organisations. In particular, pharmaceutical and medical device companies provide direct funding to some of these studies. For an up-to-date list of our conflicts of interest see https://dcr.unibe.ch/services/declaration_of_interest/index_eng.html. E. Barbato declares grants or contracts from Pfizer; honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Insight Lifetech; and participation on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Abbott, outside the submitted work. N. Kukreja has received grants from DalCor Pharma, the Population Health Research Institute, the European Cardiovascular Research Institute, and Daiichi Sankyo; and has received personal fees from AstraZeneca and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. A. Tirouvanziam reports receiving consultant and proctor (TAVI) fees from Edwards Lifesciences, outside the submitted work. P.C. Smits reports personal consulting or speaker fees from Terumo, Abiomed, and OpSense; grants and personal consulting fees from Abbott, MicroPort, and Daiichi Sankyo; and grants from SMT, outside the submitted work. M. Valgimigli reports grants and/or personal fees from AstraZeneca, Terumo, Alvimedica/CID, Abbott, Daiichi Sankyo, Bayer, CoreFlow, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals, Universität Basel Department Klinische Forschung, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb SA, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Vesalio, Novartis, Chiesi, and PhaseBio, outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this paper to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.