Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

As post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) bleeding is increasingly recognised as a prognostically meaningful event1, antiplatelet strategies that minimise bleeding risks while preventing recurrent ischaemic events have been extensively studied in large-scale randomised controlled trials2. The totality of the evidence from these studies, which generally excluded patients at high bleeding risk (HBR), shows that short dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) durations (1-3 months) after PCI reduce bleeding and are safe in terms of recurrent ischaemic events, even after a myocardial infarction34. In the vulnerable population of HBR patients, which is in theory the most likely to benefit from DAPT de-escalation, only recently have clinical practice guidelines incorporated recommendations to reduce DAPT duration56. The HBR-specific guideline recommendations were mainly based on the MASTER DAPT trial, which showed that an abbreviated one-month DAPT duration strategy after PCI decreased the risk of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding, and was non-inferior in terms of net adverse clinical events (NACE) and major adverse cardiac or cerebral events (MACCE), compared with at least two additional months of DAPT in patients at HBR7. These findings were consistent in multiple high ischaemic risk subgroups, which is reassuring for the adoption of a more liberal approach to abbreviated DAPT in HBR patients. Given this background, it is thus expected that the practice of prescribing short DAPT durations after PCI, both in HBR and non-HBR patients, will gradually percolate into routine clinical practice and become increasingly mainstream for most patients8.

Patients presenting with overlapping ischaemic and bleeding risk factors, however, represent a particularly challenging population in respect to the choice of antiplatelet regimens. Among those, chronic kidney disease (CKD) increases the risk of bleeding after PCI, while simultaneously representing a marker of adverse prognosis in terms of recurrent ischaemic events9, complicating the risk/benefit assessment for DAPT de-escalation.

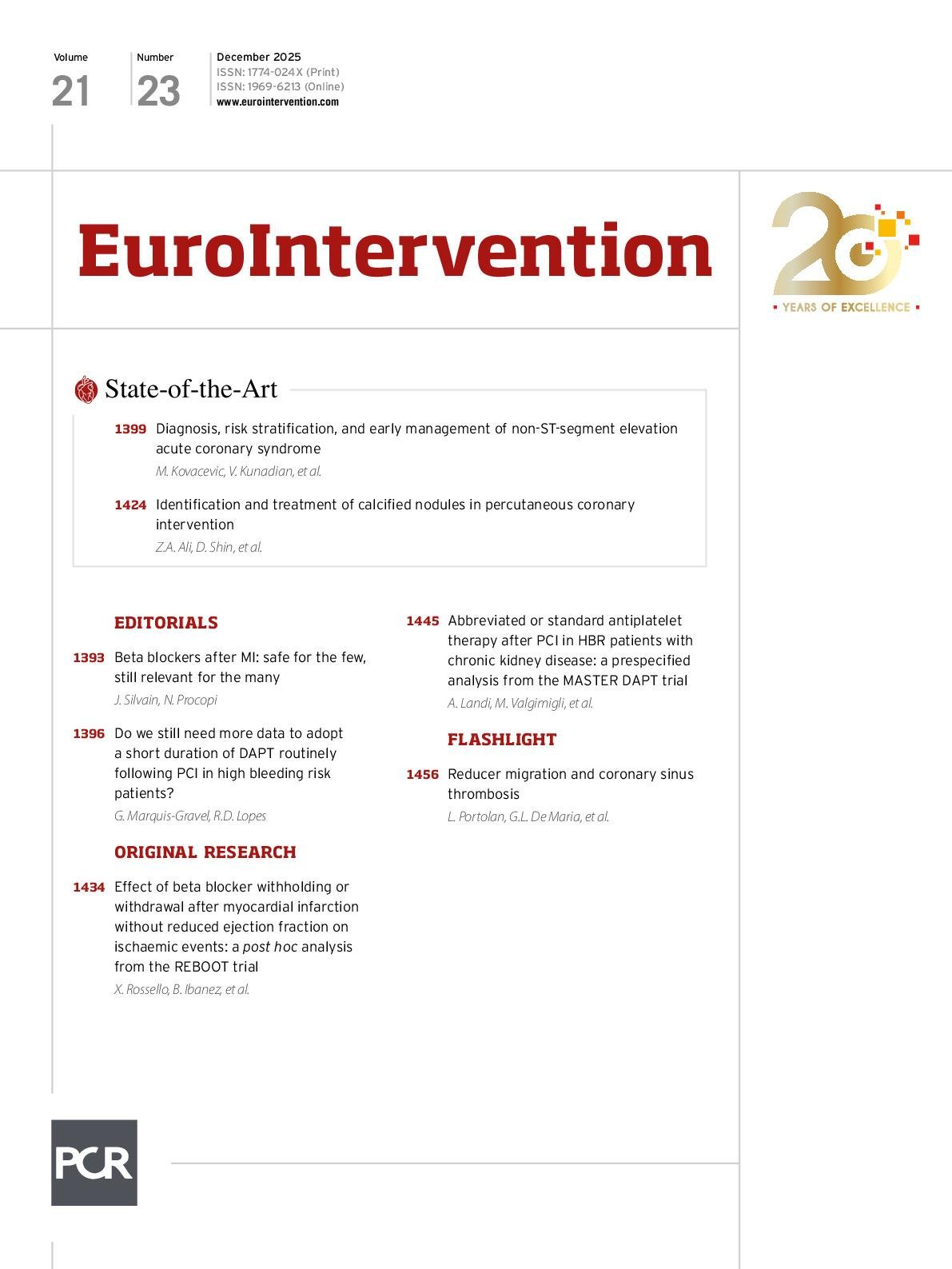

In this issue of EuroIntervention, Landi et al present a prespecified analysis of the MASTER DAPT trial evaluating the treatment effects of abbreviated versus standard antiplatelet therapy duration in HBR patients according to the presence of concomitant CKD (defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] <60 mL/min/1.73 m2)10.

A total of 31% of MASTER DAPT participants had CKD, highlighting the high prevalence of this high-risk population among PCI patients. Despite randomisation not being stratified by CKD status, the types and combinations of antiplatelet agents were generally well balanced between CKD and non-CKD participants. NACE, MACCE, and all-cause death were significantly more frequent at 11 months in patients with CKD compared with non-CKD patients, and the contrast was accentuated with increasing degree of renal dysfunction. Rates of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding were not significantly different between both groups, but when bleeding was assessed with the standardised Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) definition (BARC 3 or 5 bleeding), the event rates were higher in patients with CKD. In MASTER DAPT, the presence of CKD therefore conferred a higher risk of both bleeding and ischaemic events, consistent with previous evidence9

The key finding of this analysis is that there was no significant interaction between CKD status and treatment effect of abbreviated DAPT for NACE (pinteraction=0.78), MACCE (pinteraction=0.44), major or clinically relevant non-major bleedings (pinteraction=0.59), and secondary outcomes. In line with the Academic Research Consortium minor and major HBR criteria, the hypothesis was tested in post hoc stratified subgroups with mild-to-moderate CKD (eGFR ≥30 but <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and severe CKD (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2). The findings of the latter were consistent with the main analysis, but the absolute reduction in bleeding with abbreviated DAPT was of a higher magnitude in the subgroup of patients with severe CKD. Even if the comparisons were underpowered to detect significant treatment effects with an abbreviated DAPT duration within the CKD subgroup, it is reassuring that its direction was in favour of abbreviated DAPT for both ischaemic and bleeding endpoints.

The lack of interaction between abbreviated DAPT duration and baseline renal function in terms of both ischaemic and major bleeding events observed in this secondary analysis is consistent with previous evidence from trials enrolling non-HBR patients39, adding more evidence to the field. Assessing the totality of the evidence from CKD subgroups of randomised trials evaluating short DAPT duration strategies, in addition to reassuring secondary analyses in high-ischaemic risk subgroups of MASTER DAPT (complex PCI, myocardial infarction at baseline, diabetes), a one-month DAPT strategy should be strongly considered as a reasonable and safe strategy after PCI in most patients with CKD.

The results of this secondary analysis need to be examined within the larger context of the accumulating evidence from randomised controlled trials, all pointing in the same direction favouring shorter DAPT durations (1-3 months) to reduce bleeding without jeopardising ischaemic risk in patients with and without HBR4. A 1-month DAPT duration, however, seems to represent the ultimate frontier after PCI given the recent results of the NEO-MINDSET trial, the first properly powered study to evaluate the impact of early aspirin discontinuation (with continuation of potent P2Y12 inhibitor alone) <4 days after hospital admission11. In this trial, the former strategy was not non-inferior to a 12-month DAPT strategy in terms of the composite of death from any cause, myocardial infarction, stroke, or urgent target vessel revascularisation, although the rates of major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding events were nominally reduced with the short DAPT strategy.

Nevertheless, evidence continues to consistently favour a 1-3-month DAPT duration after PCI in most patients. Recently, the TARGET-FIRST trial again showed that among patients with a myocardial infarction who underwent complete revascularisation with PCI, 1-month DAPT is safer in terms of bleeding, and non-inferior in terms of net adverse clinical and cerebrovascular events, compared with standard 12-month DAPT3. Even if high ischaemic risk subgroup analyses of the many trials evaluating the impact of a 1-3-month DAPT duration are underpowered, their results point to the same direction suggesting an overall clinical superiority of this strategy.

In this context, do we really need more data to standardise the practice of prescribing a 1-month DAPT duration as a default strategy in most patients after PCI, regardless of HBR status and indication for PCI? Probably not.

Acknowledgements

G. Marquis-Gravel is a Junior 2 Clinical Research Scholar of the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé (grant #367177).

Conflict of interest statement

G. Marquis-Gravel reports receiving honoraria from Novartis, JAMP Pharma, and Metapharm; support for attending meetings from Novartis; and serving as Co-Chair of the Canadian Guidelines on Antiplatelet Therapy, and as Quebec Representative for the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology. R.D. Lopes reports grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis; consulting fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk; and honoraria from Pfizer and Daiichi Sankyo.