Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

Abstract

Background: Photon-counting detector computed tomography (PCD-CT) offers enhanced spatial resolution and reduced blooming artefacts, potentially improving the evaluation of stented coronary vessels.

Aims: This study aimed to assess the diagnostic performance of dual-source PCD-CT in detecting obstructive in-stent restenosis (ISR).

Methods: We identified consecutive patients with prior coronary stent implantation who underwent clinically indicated coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) with PCD-CT and subsequent invasive coronary angiography within 90 days between 2023 and 2024. Obstructive ISR (≥50% diameter stenosis) was determined by visual assessment of CCTA and invasive quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) in a blinded fashion. The diagnostic performance of CCTA for ISR was compared with that of QCA.

Results: A total of 283 stented lesions from 171 patients were included. Of these, only 3 lesions (1.1%) were deemed indeterminate by PCD-CT. Using invasive QCA as the reference standard, PCD-CT demonstrated a lesion-level sensitivity of 80.0%, specificity of 90.4%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 58.2%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 96.4%, and an overall diagnostic accuracy of 88.9% for detecting obstructive ISR. In a subgroup analysis according to the stent diameter (<3.00 mm [n=83] vs ≥3.00 mm [n=108]), there were no significant differences in sensitivity (87.5% vs 86.7%; p=1.00), specificity (93.3% vs 92.5%; p=1.00), PPV (58.3% vs 65.0%; p=1.00), NPV (98.6% vs 97.7%; p=1.00), or overall diagnostic accuracy (92.8% vs 91.7%; p=1.00), respectively.

Conclusions: PCD-CT demonstrated good diagnostic performance for evaluating obstructive ISR using QCA as the reference standard, regardless of stent diameter.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is increasingly used as a first-line diagnostic modality for patients with chest pain12. However, its effectiveness in assessing in-stent restenosis (ISR), particularly in smaller stents, remains limited due to artefacts from metallic struts and calcium3. Photon-counting detector computed tomography (PCD-CT) is an advanced CT technology that may enhance the evaluation of stented lesions. Unlike conventional energy-integrating detector CT (EID-CT), PCD-CT utilises semiconductor detectors to directly convert photon energy into electronic signals, eliminating the need for septa required by scintillating detectors, thereby improving spatial resolution and reducing electronic noise and blooming artefacts4. These advantages have been demonstrated in clinical practice, with a recent large-scale study showing improved diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in evaluating patients with suspected coronary artery disease compared with EID-CT5. Although preliminary studies have suggested the feasibility of PCD-CT in assessing coronary stents67, these were limited by small sample sizes and the inclusion of few patients with ISR. Therefore, this study sought to assess the diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in detecting obstructive ISR in routine clinical practice.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a retrospective, single-centre study that included all consecutive patients with prior coronary stent implantation who underwent clinically indicated CCTA with PCD-CT and subsequent invasive coronary angiography (ICA) within 90 days between January 2023 and December 2024 at St. Francis Hospital & Heart Center, Roslyn, NY, USA. Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained through chart review. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Francis Hospital & Heart Center. Informed consent was waived due to the minimal risk involved.

CCTA image acquisition and analysis

Details of PCD-CT image acquisition have been described previously5. PCD-CT was performed using the dual-source NAEOTOM Alpha (Siemens Healthineers). Collimation was 144×0.4 mm in standard mode and 120×0.2 mm in ultrahigh-resolution (UHR) mode, with reconstruction slice thicknesses of 0.4 mm and 0.2 mm, respectively. Scans were acquired at a tube voltage of 140 kVp per the manufacturer’s recommendations5. All patients received 0.4-0.8 mg of sublingual nitroglycerine as well as oral metoprolol (50-100 mg) and/or intravenous (IV) metoprolol (5-10 mg boluses every 5 minutes, up to a maximum of 40 mg) as per institutional protocol to achieve a target heart rate of <65 bpm. A total volume of 60-100 mL of iso-osmolar, isotonic IV contrast was injected at a rate of 4-6 mL/s5. Standard reconstructions were performed using medium-smooth kernels and sharper kernels for all patients, which were available for the CT interpreting physician5. CCTA images were analysed by cardiologists with Level 3 certification or equivalent expertise in cardiac CT, following the guidelines of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography8. Luminal stenosis was visually assessed and classified using the Coronary Artery Disease Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS)9. Stented segments with ≥50% diameter stenosis (DS) were categorised as obstructive ISR. If the severity of stenosis could not be confidently determined because of suboptimal image quality or artefacts, the lesion was categorised as “indeterminate”5. To assess interobserver variability, a second imaging cardiologist independently analysed the first 60 stented segments in a blinded fashion.

Quantitative coronary angiography

All ICA was performed using standard techniques. In baseline ICA images, all stented lesions were analysed using quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) with dedicated software (Cath-QCA [TOMTEC]) by experienced analysts blinded to the CCTA findings. Overlapping stents were considered as a single lesion. Obstructive ISR was defined as a DS of ≥50%, as assessed by QCA10.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]), depending on the distribution tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test, and were compared using the t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables are presented as number and proportion (%) and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in detecting obstructive ISR was evaluated at both the stented-lesion and patient levels, excluding lesions with indeterminate readings, using QCA as the reference standard. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and overall diagnostic accuracy were derived from two-by-two contingency tables. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) was also calculated. To evaluate the impact of stent diameter on diagnostic performance, subgroup analyses were conducted among patients with available stent information, stratified by the mean stent diameter of the stented lesion (<3.00 mm vs ≥3.00 mm). Diagnostic performance metrics were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test, and AUC-ROC comparisons were conducted using the DeLong test. Interobserver variability between imaging cardiologists in diagnosing ISR using PCD-CT was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and Stata 18.0 SE (StataCorp).

Results

Study population

A total of 398 consecutive patients with prior coronary stent implantation who underwent clinically indicated CCTA between 2023 and 2024 were identified. Among them, 184 patients subsequently underwent ICA within 90 days. After excluding 13 patients owing to missing or poor-quality coronary angiography images for QCA, the final study cohort consisted of 171 patients with 283 stented lesions (Supplementary Figure 1). The mean age was 67.5±9.8 years, with 58 patients (33.9%) being female and 57 patients (33.3%) having diabetes mellitus (Table 1). The majority of patients (81.3%) underwent PCD-CT in UHR mode. The median dose-length product (DLP) was 791.0 mGy·cm (IQR 677.5-905.0 mGy·cm), and the total effective radiation dose from CCTA was 11.1 mSv (IQR 9.5-12.7 mSv). The indications for invasive coronary angiography are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1. Patient demographics and CT parameters.

| N=171 | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 67.5±9.8 |

| Female | 58 (33.9) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1 (25.2-31.2) |

| Hypertension | 139 (81.3) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 139 (81.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 (33.3) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.97 (0.84-1.14) |

| Chronic kidney disease* | 35 (20.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 20 (11.7) |

| Prior MI | 41 (24.0) |

| CABG | 12 (7.0) |

| CT acquisition parameters | |

| UHR mode | 139 (81.3) |

| Average heart rate, bpm | 59.0 (55.0-64.0) |

| Total contrast, mL | 95.0 (90.0-95.0) |

| Peak voltage, kVp | 140 (140-140) |

| Dose-length product, mGy × cm | 791.0 (677.5-905.0) |

| Total radiation, mSv | 11.1 (9.5-12.7) |

| Data are presented as mean±standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or n (%). *Defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. BMI: body mass index; bpm: beats per minute; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CT: computed tomography; MI: myocardial infarction; UHR: ultrahigh-resolution | |

Stented segment characteristics

Stented lesions were most commonly located in the left anterior descending artery (44.5%), followed by the right coronary artery (32.5%) (Table 2). Among them, 3 stented lesions (1.1%) were classified as indeterminate by CCTA, and 55 (19.4%) were identified as having obstructive ISR. There was substantial interobserver agreement, with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.47-1.00). By QCA, the median DS was 26.7% (IQR 17.3-38.3%), with 41 lesions (14.5%) classified as obstructive ISR (DS ≥50%). Among patients with available stent information (n=193), most stented lesions (70.0%) had a single stent (median: 1 [IQR 1-2]). The median stent diameter per stented lesion was 3.00 mm (IQR 2.75-3.50 mm), with a total stent length of 23.0 mm (IQR 15.0-35.0 mm) (Table 2). The majority (94.2%) of stents with available data had a strut thickness <100 μm. Stented lesions with a mean stent diameter of ≥3.00 mm (n=110) were more frequently located in the right coronary artery than those with a mean stent diameter of <3.00 mm (n=83) (Table 3). The mean stent diameter of the smaller-stent group was 2.62 mm (IQR 2.50-2.75 mm), whereas that of larger-stent group was 3.33 mm (IQR 3.00-3.50 mm). The rate of indeterminate CCTA readings was similar between the two groups (<3.00 mm: 0% vs ≥3.00 mm: 1.8%).

Table 2. Characteristics of stented lesions.

| Stented lesions | N=283 |

|---|---|

| Stented vessel | |

| Left main | 4 (1.4) |

| Left main trunk | 1 (0.4) |

| Left main bifurcation | 3 (1.1) |

| Left anterior descending artery | 126 (44.5) |

| Left circumflex artery | 61 (21.6) |

| Right coronary artery | 92 (32.5) |

| Stented segment | |

| Proximal segment only | 57 (20.1) |

| Including mid- to distal segments or branches | 226 (79.9) |

| Stent information, per stented lesion* (n=193) | |

| Number of stents | 1 (1-2) |

| Mean diameter of stents, mm | 3.00 (2.75-3.50) |

| <3.0 mm | 83/193 (43.0) |

| ≥3.0 mm | 110/193 (57.0) |

| Total stent length, mm | 23.0 (15.0-35.0) |

| Strut thickness† | |

| <100 µm | 178 (94.2) |

| ≥100 µm | 11 (5.8) |

| CCTA findings | |

| Diameter stenosis | |

| 0% | 85 (30.0) |

| 1-24% | 72 (25.4) |

| 25-49% | 68 (24.0) |

| 50-69% | 28 (9.9) |

| 70-99% | 19 (6.7) |

| 100% | 8 (2.8) |

| Indeterminate | 3 (1.1) |

| In-stent restenosis (≥50%) | 55 (19.4) |

| QCA findings | |

| Diameter stenosis, % | 26.7 (17.3-38.3) |

| In-stent restenosis (≥50%) | 41 (14.5) |

| Data are presented as median (interquartile range), n/N (%), or n (%). *Overlapped stents were considered to be one stented lesion. Among 283 stented lesions, no stent information was available for 90 lesions. †Stent type and strut thickness data were available for 189 stented lesions. CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography | |

Table 3. Characteristics of stented lesions according to the mean stent diameter.

| Mean stent diameter | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| <3.0 mm (N=83) | ≥3.0 mm (N=110) | ||

| Stented vessel | <0.001 | ||

| Left main | 0 (0) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Left anterior descending artery | 40 (48.2) | 40 (36.4) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 28 (33.7) | 15 (13.6) | |

| Right coronary artery | 15 (18.1) | 52 (47.3) | |

| Stented segment | <0.001 | ||

| Proximal segment only | 5 (6.0) | 37 (33.6) | |

| Including mid- to distal segments or branches | 78 (94.0) | 73 (66.4) | |

| Stent information | |||

| Number of stents | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) | 0.02 |

| Mean stent diameter, mm | 2.62 (2.50-2.75) | 3.33 (3.00-3.50) | <0.001 |

| Total stent length, mm | 23.0 (15.0-39.5) | 22.5 (15.0-33.0) | 0.57 |

| CCTA findings | |||

| Indeterminate | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) | NA |

| In-stent restenosis (≥50%) | 12 (14.5) | 20 (18.2) | 0.58 |

| QCA findings | |||

| Diameter stenosis, % | 27.6 (16.7-38.8) | 24.7 (13.3-34.9) | 0.33 |

| In-stent restenosis (≥50%) | 8 (9.6) | 16 (14.5) | 0.42 |

| Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%). CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; NA: not available; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography | |||

Diagnostic performance of PCD-CT for ISR

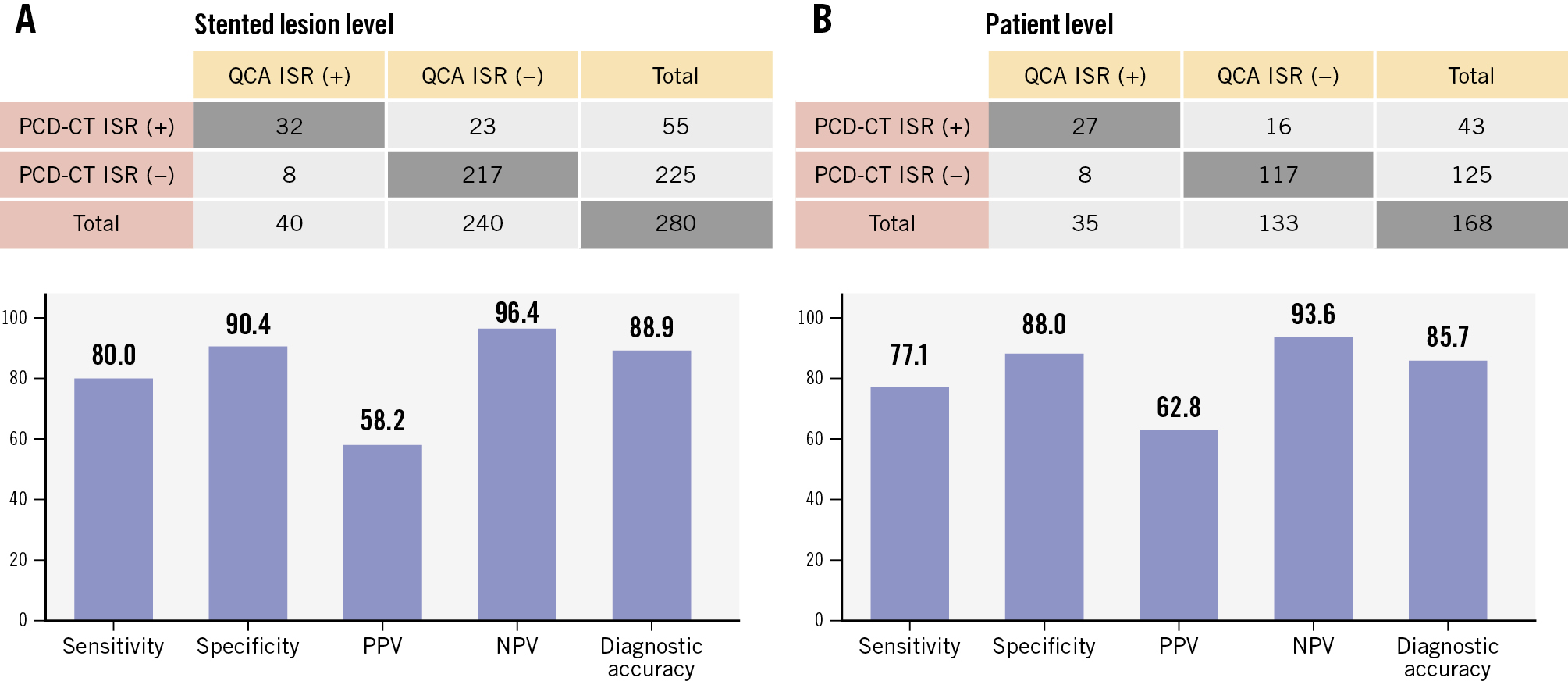

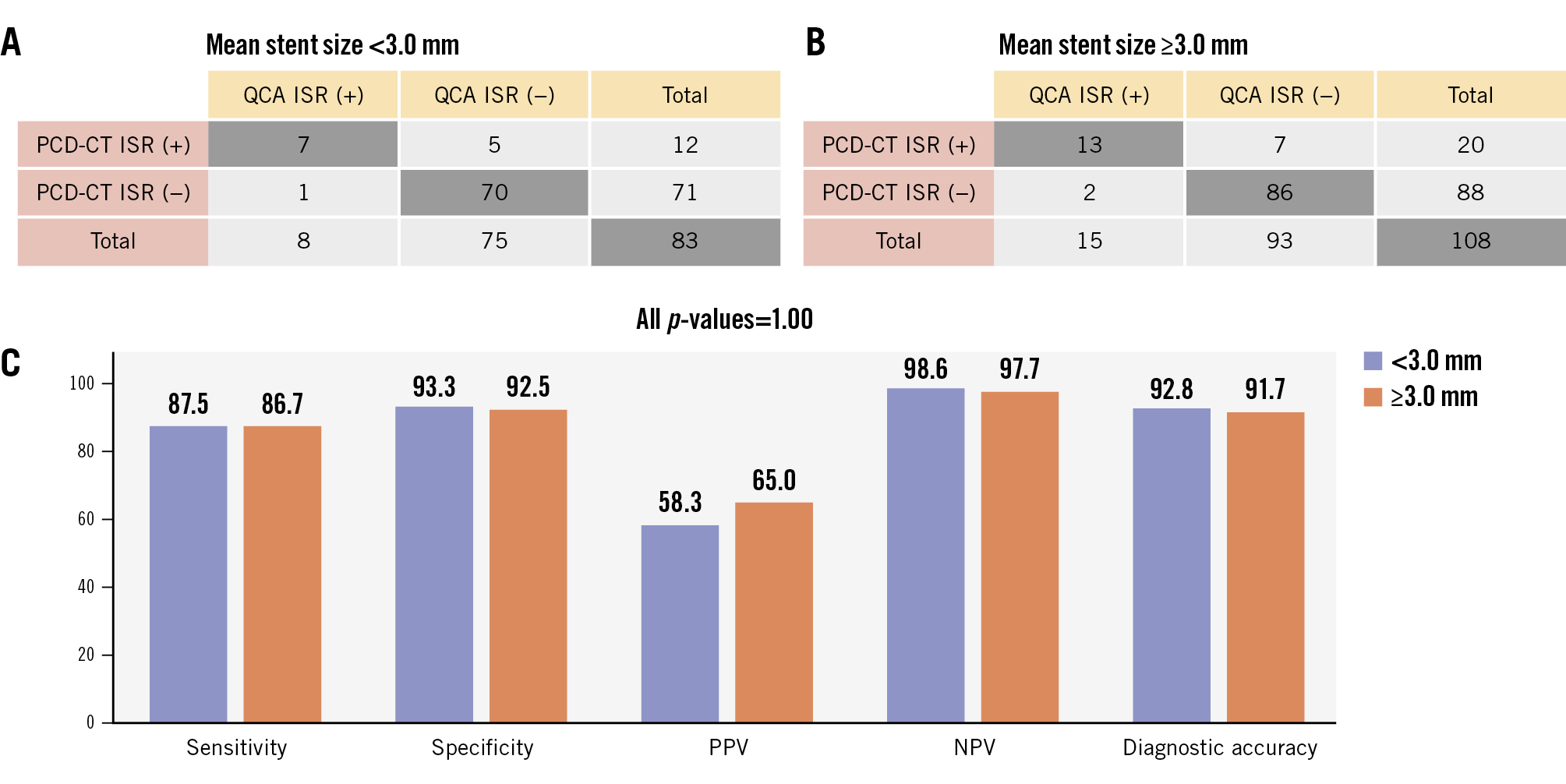

Among stented lesions not classified as indeterminate (280 lesions from 168 patients), PCD-CT demonstrated good diagnostic performance for obstructive ISR at both the lesion and patient levels, using QCA as the reference standard (Figure 1). At the lesion level, PCD-CT achieved sensitivity of 80.0% (95% CI: 65.2-89.5), specificity of 90.4% (95% CI: 86.0-93.5), PPV of 58.2% (95% CI: 45.0-70.3), NPV of 96.4% (95% CI: 93.1-98.2) and overall diagnostic accuracy of 88.9% (95% CI: 84.7-92.1) with an AUC-ROC of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.79-0.92). At the patient level, PCD-CT demonstrated sensitivity of 77.1% (95% CI: 61.0-87.9), specificity of 88.0% (95% CI: 81.4-92.5), PPV of 62.8% (95% CI: 47.9-75.6), NPV of 93.6% (95% CI: 87.9-96.7), and overall diagnostic accuracy of 85.7% (95% CI: 79.6-90.2) with an AUC-ROC of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.75-0.90). The characteristics of false positive cases (23 stented lesions and 16 patients) are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. The majority of these cases (78.3%) were graded as 50-69% stenosis by PCD-CT, suggesting a mild overestimation of lesion severity. Subgroup analysis based on mean stent diameter (<3.00 mm [n=83] vs ≥3.00 mm [n=108]) demonstrated comparable lesion-level diagnostic performance of PCD-CT for detecting obstructive ISR (AUC-ROC 0.90 [95% CI: 0.78-1.00] vs 0.89 [95% CI: 0.80-0.99], respectively; p=0.92), with no significant differences in any metrics (p=1.00) between the two stent size groups (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Diagnostic performance of PCD-CT for obstructive ISR using QCA as the reference standard. Two-by-two contingency tables comparing the presence of obstructive ISR as assessed by PCD-CT and QCA are presented at (A) the stented-lesion level and (B) the patient level. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall diagnostic accuracy of PCD-CT are illustrated in bar graphs. ISR: in-stent restenosis; NPV: negative predictive value; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; PPV: positive predictive value; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography.

Figure 2. Stented lesion-level diagnostic performance of PCD-CT for ISR using QCA as the reference standard according to stent size. Two-by-two contingency tables comparing the presence of obstructive ISR as assessed by PCD-CT and QCA are presented based on mean stent diameter: (A) <3.00 mm and (B) ≥3.00 mm. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall diagnostic accuracy of PCD-CT are depicted in bar graphs (C). ISR: in-stent restenosis; NPV: negative predictive value; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; PPV: positive predictive value; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography.

Discussion

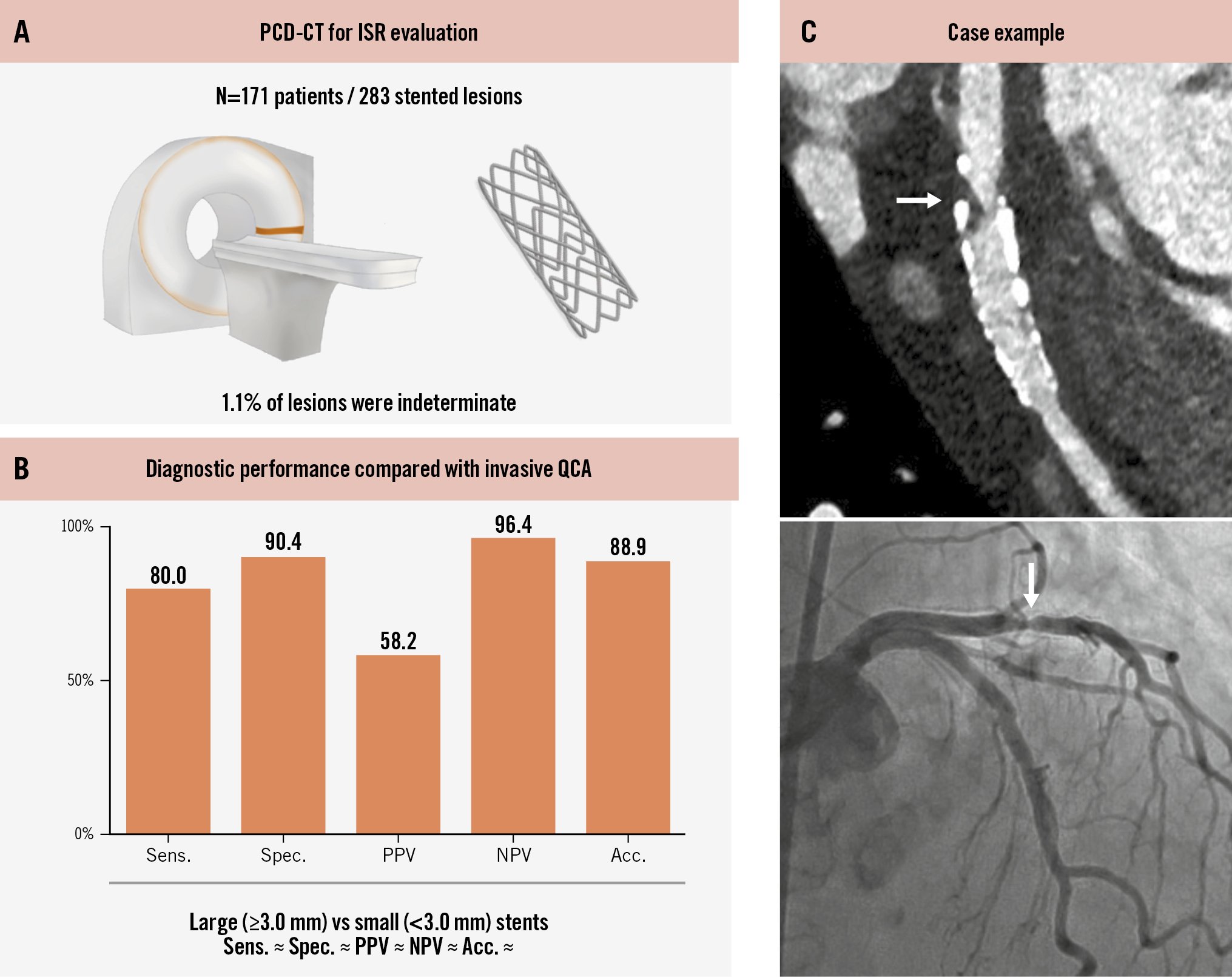

In this study, we assessed the diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in detecting obstructive ISR. Our key findings include the following: (1) among 171 consecutive patients with 283 stented lesions evaluated by PCD-CT followed by ICA, the vast majority of stented lesions were assessable by CCTA; (2) using QCA as the reference standard, PCD-CT demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance for obstructive ISR at both the stented-lesion and patient levels with high specificity and NPV; (3) the diagnostic accuracy of PCD-CT for obstructive ISR was similar for stented lesions with an average stent diameter of ≥3.00 mm and those <3.00 mm (Central illustration). Advances in PCD-CT have enhanced spatial resolution while reducing blooming artefacts and image noise compared with EID-CT, offering significant advantages in evaluating coronary artery disease4. In a recent study, the use of PCD-CT compared with EID-CT was associated with a lower referral rate for invasive coronary angiography and a higher rate of revascularisation among referred patients5. However, the diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in evaluating ISR remains incompletely understood, with only a few small studies published to date67. Hagar et al analysed 44 stents from 18 patients undergoing CCTA with PCD-CT, reporting a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 87.2-92.3%, compared with ICA7. However, this study primarily included patients undergoing CCTA prior to transcatheter aortic valve implantation assessment and included only five ISR cases. Qin et al reported similar findings among 25 stents in 12 patients, with a sensitivity of 75.0% and a specificity of 90.1%6. Beyond their small sample sizes, both studies relied on visual estimation of angiographic stenosis severity as the reference standard – a method known for its low reproducibility11. The present study included 283 stented lesions from 171 consecutive patients who underwent clinically indicated CCTA with PCD-CT in routine clinical practice. In this all-comers population, PCD-CT demonstrated excellent diagnostic performance for evaluating ISR, using QCA as the reference standard. Although the PPV remained modest at both the lesion and vessel levels, PCD-CT was particularly effective in ruling out obstructive ISR. This finding aligns with our recent study in patients without prior stents5, further supporting the potential role of PCD-CT in patients with suspected obstructive coronary artery disease, whether in unstented or stented segments. Earlier evidence from EID-CT suggested that the diagnostic value of CCTA is limited in smaller stents312. The 2010 multisocietal Appropriate Use Criteria classified CCTA as “appropriate” only for asymptomatic patients with prior left main coronary stents ≥3.00 mm in diameter and “inappropriate” for stents <3.00 mm or of unknown diameter13. In contrast, the latest consensus from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography classified CCTA as “may be appropriate” for symptomatic patients with stents <3.00 mm14. In our analysis, we found that PCD-CT demonstrated consistent diagnostic performance for stents <3.00 mm compared with those ≥3.00 mm. These findings demonstrate that CCTA with PCD-CT is a viable option for evaluating patients with prior stent implantation, regardless of stent size (Figure 3, Figure 4) and suggest that further updates to these Appropriate Use Criteria may be warranted when PCD-CT is available.

Central illustration. Assessment of obstructive ISR using PCD-CT. Among 283 stented lesions from 171 patients who underwent PCD-CT followed by invasive coronary angiography (A), PCD-CT showed good diagnostic performance for the detection of ISR using QCA as the reference standard (B). C) Case example. White arrows represent focal ISR in the proximal stent edge. acc: accuracy; ISR: in-stent restenosis; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography; sens: sensitivity; spec: specificity.

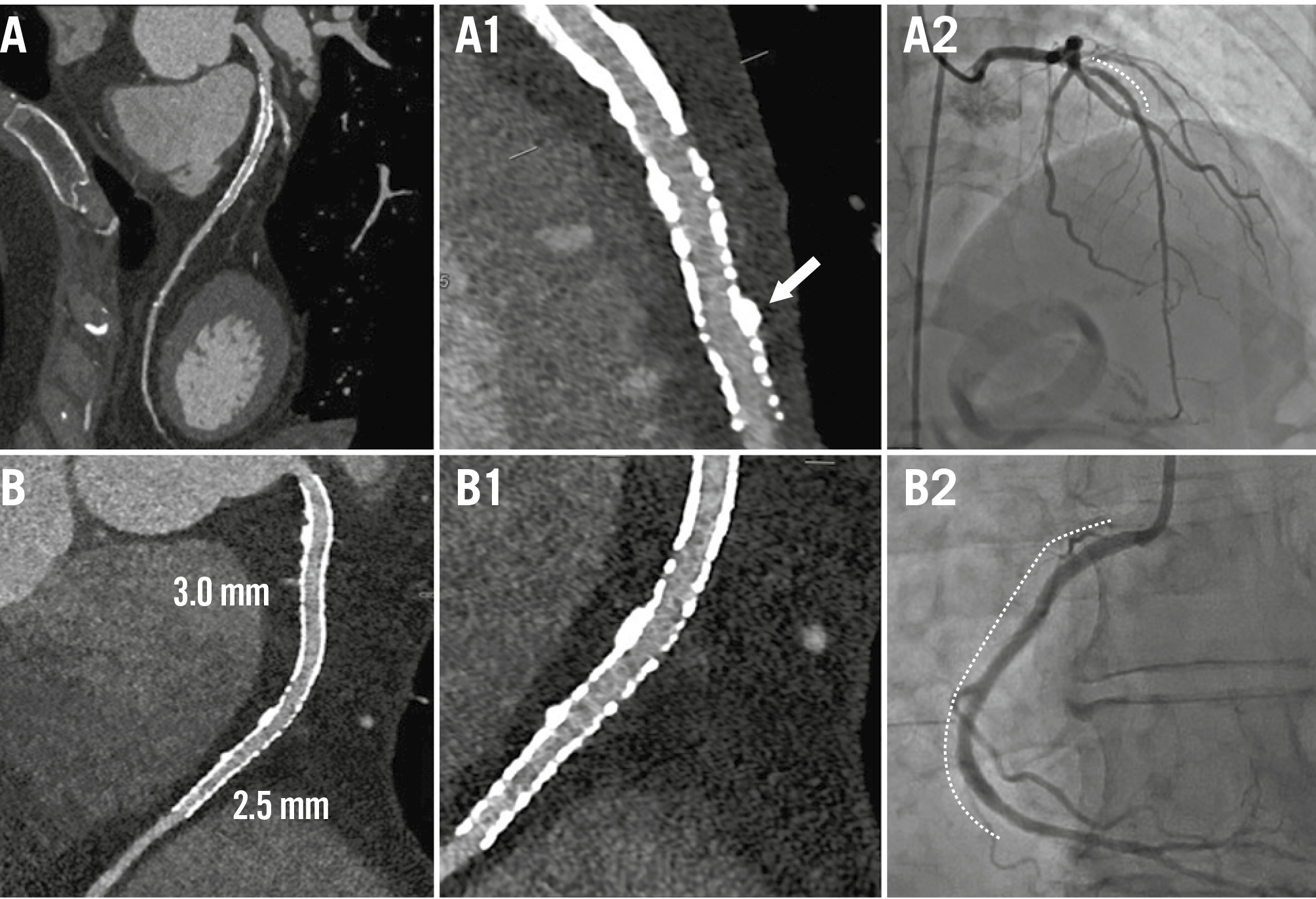

Figure 3. Examples of non-ISR cases. Case examples without ISR are presented using PCD-CT in UHR mode (UHR reconstruction: 0.2 mm slice, BV68 sharp kernel, quantum iterative reconstruction algorithm 4) and ICA. A) CCTA of the LAD in a patient with a prior DES implantation in the mid-LAD (Resolute [Medtronic]; 3.00×18 mm) and (B) CCTA of the RCA with two prior DES implants (Resolute Onyx [also Medtronic]; 3.0×38 mm proximally and 2.5×38 mm distally). A1) CCTA showed a patent stent in the mid-LAD with mild calcified plaque external to the stent (white arrow), confirmed by subsequent ICA (A2; dotted line). B1) CCTA demonstrated patent stents with clear visualisation of the stent lumen, confirmed by ICA (B2; dotted line). Dotted lines on the ICA indicate the stents. CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; DES: drug-eluting stent; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; ISR: in-stent restenosis; LAD: left anterior descending artery; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; RCA: right coronary artery; UHR: ultrahigh-resolution.

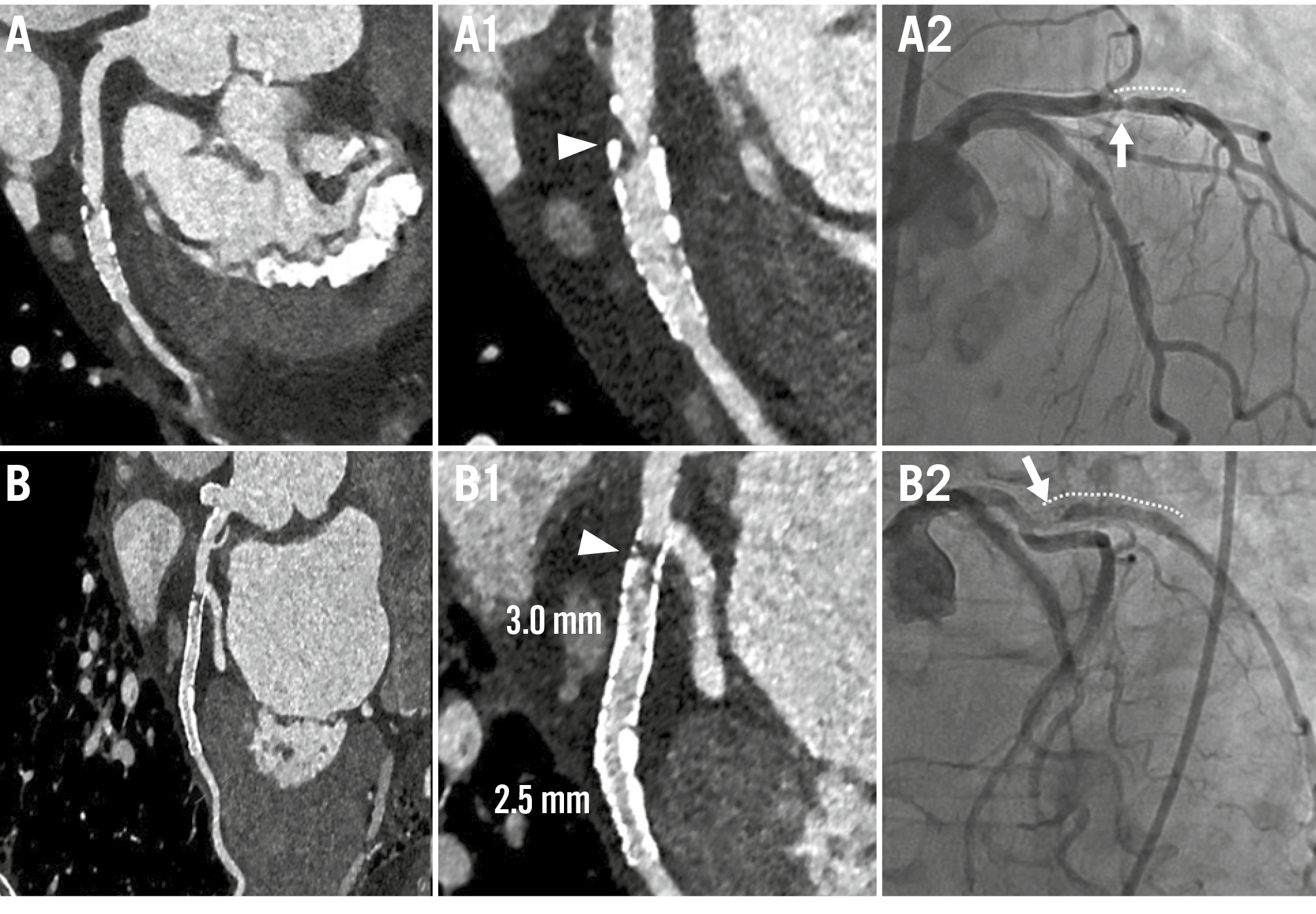

Figure 4. Examples of ISR cases. Case examples of ISR are presented using PCD-CT in UHR mode (UHR reconstruction: 0.2 mm slice, BV68 sharp kernel, quantum iterative reconstruction algorithm 4) and ICA. A) CCTA of a patient with a prior DES (type and size unknown) in the first obtuse marginal branch, who presented with chest pain. A1) CCTA revealed obstructive ISR at the proximal stent edge (white arrowhead), confirmed by ICA, which showed a 59.2% diameter stenosis by QCA (A2; white arrow). B) CCTA of a patient with two DES implants (XIENCE [Abbott]; 2.75×12 mm proximally and 2.50×12 mm distally) in the first obtuse marginal branch. B1) CCTA demonstrated obstructive ISR at the proximal stent edge (white arrowhead), confirmed by ICA, which revealed subtotal occlusion (B2; white arrow). Dotted lines on the ICA indicate the stents. CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography; DES: drug-eluting stent; ICA: invasive coronary angiography; ISR: in-stent restenosis; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; QCA: quantitative coronary angiography; UHR: ultrahigh-resolution

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, it was subject to inherent biases. In particular, not all patients underwent ICA following CCTA, and the decision to proceed with ICA was based on clinical judgment rather than standardised criteria. This may have introduced verification bias and impacted the assessment of diagnostic performance, especially in underestimating false negatives among patients who were not referred for ICA. However, the NPV of CCTA is generally high, as demonstrated in the present study as well. Second, while this analysis represents the largest population studied to date, the number of ISR cases remains limited. Third, CCTA images were visually analysed, which may introduce reader subjectivity. However, these images were evaluated by the same group of experienced, board-certified CT readers as part of routine clinical practice, and interobserver agreement among the readers was substantial. In addition, the primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the diagnostic performance of PCD-CT in real-world clinical practice, where visual assessment of CCTA images remains the standard approach. While quantitative analysis of PCD-CT images could enhance objectivity, its application to in-stent assessment remains to be validated and may warrant future investigation. In contrast, ICA images, which served as the reference standard, were objectively evaluated using blinded QCA analysis. Fourth, angiographic DS was assessed using two-dimensional QCA, as three-dimensional QCA was not available. In addition, intravascular imaging was available in only a limited number of patients. Fifth, although institutional policy recommends UHR mode for patients with prior stents, PCD-CT was performed in both UHR (81.3%) and conventional modes (18.7%) due to high heart rates, arrhythmias, and the inability of patients to hold their breath for the scan time required for UHR, which represents a spectrum of real-life clinical patients. Sixth, stent information was unavailable in approximately one-third of cases, and among those with available data, the majority had a strut thickness <100 μm. Therefore, the present findings may not be applicable to stents with a strut thickness ≥100 μm. Finally, as a single-centre study conducted in a high-volume cardiac PCD-CT programme, the results may not be generalisable to institutions with different scanning protocols or practice patterns. Despite these limitations, this study provides the largest real-world evaluation of PCD-CT for ISR, offering valuable early insights into its diagnostic performance and clinical utility. A future study will evaluate the feasibility of using PCD-CT to assess ISR mechanisms and tissue characteristics, using angiography and intravascular imaging as reference standards.

Conclusions

In this large-scale, single-centre study, PCD-CT demonstrated good diagnostic performance for evaluating obstructive ISR, particularly with high specificity and NPV, independent of stent diameter. These findings suggest that PCD-CT technology may improve the management of patients with prior stents. Further multicentre studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to validate these findings.

Impact on daily practice

Photon-counting detector computed tomography (PCD-CT) demonstrated good diagnostic performance for evaluating in-stent restenosis in patients with prior coronary stents. PCD-CT can be used in patients with suspected obstructive coronary artery disease, whether in unstented or stented segments.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Shin reports a research grant from SCAI/Abbott. R.H.J.A. Volleberg reports fellowship grants from the Foundation “De Drie Lichten” and the Netherlands Heart Institute. R. Parikh has been a consultant to HeartFlow and Siemens. J.M. Khan received consulting/proctorship fees from Abbott, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic; he received institutional grant support from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Philips; and he has equity options in Transmural Systems and Cuspa Medical. D.J. Cohen reports institutional research grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, Boston Scientific, CathWorks, Philips, and Zoll Medical; and he receives consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. N. van Royen reports institutional research grants from Abbott, Philips, Biotronik, and Medtronic; and speaker honoraria from MicroPort, Bayer, Abbott, and RainMed. C. Collet reports receiving research grants from Biosensors, Coroventis Research, Medis Medical Imaging, Pie Medical Imaging, CathWorks, Boston Scientific, Siemens, HeartFlow, and Abbott; and consultancy fees from HeartFlow, Opsens, Abbott, and Philips/Volcano. E. Shlofmitz has been a consultant to Abbott, ACIST Medical, Boston Scientific, Gentuity, Opsens Medical, Philips, Shockwave Medical, and Terumo; and he is a speaker for Amgen Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Novo Nordisk. A. Jeremias has received institutional grants and consulting fees from Abbott and Philips/Volcano; and has received consultant fees from ACIST and Boston Scientific. O.K. Khalique has been a consultant to Siemens, Philips, and HeartFlow. Z.A. Ali reports institutional grants from Abbott, Abiomed, ACIST Medical, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., Medtronic, Opsens Medical, Philips, and Shockwave Medical; personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Boston Scientific; and equity from Elucid, Lifelink, SpectraWAVE, Shockwave Medical, and Vital Connect. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this paper to declare.

Supplementary data

To read the full content of this article, please download the PDF.