Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

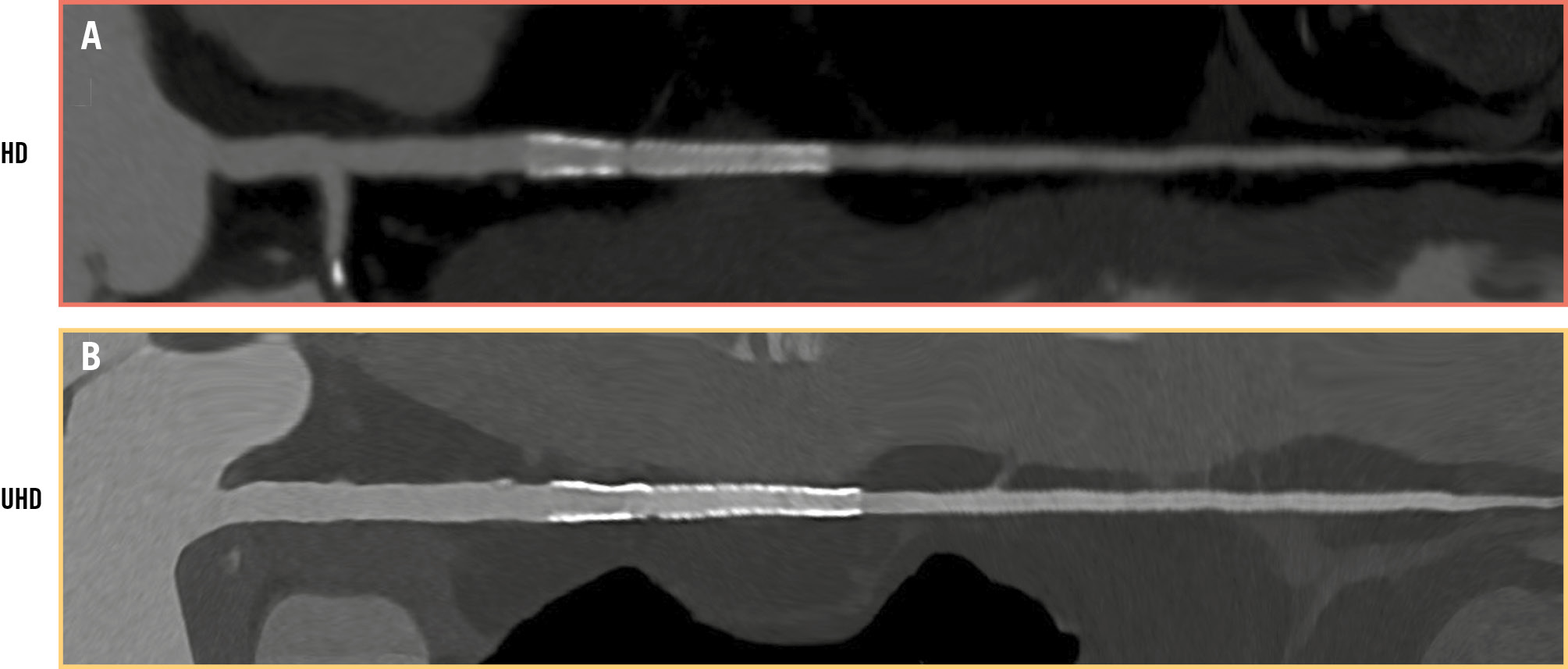

In the last decade, a large amount of evidence, including randomised clinical trials, has supported a growing clinical use of coronary computed tomography (CT) angiography (CCTA). Recent guidelines recommended this non-invasive tool as a Class I, first-line test for diagnosing coronary artery disease (CAD)1. In the evaluation of the full spectrum of CAD, however, CCTA is limited by poor image quality and artefacts related to high-density structures, such as calcified plaques and metallic stent struts, which negatively affect interpretability, specificity and diagnostic accuracy of this method compared with invasive coronary angiography (ICA)2. For stent assessment, the limited spatial resolution of conventional scanners rendered 9-10% of stents non-assessable in large CT meta-analyses. A particularly low diagnostic accuracy was found for stents with a nominal diameter <3.0 mm2. Technical developments and the introduction of CT scanners equipped with whole-heart Z-axis coverage and faster gantry rotation times, which enhance temporal resolution, reduced the rate of non-evaluable stents to 5%. However, a significantly lower diagnostic accuracy still affected the evaluation of small stents3. Photon-counting detector CT (PCD-CT) is a novel technology that has several advantages for diagnosing CAD4. In particular, by directly converting photon energies into electronic signals, PCD-CT offers significant benefits over conventional detectors, such as improved spatial resolution and decreased blooming artefacts; these allow a substantial reduction in detector pixel size and a consequent more accurate and detailed evaluation of coronary arteries and atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 1). A recent study showed that PCD-CT improved the diagnostic performance for detecting obstructive CAD, compared with conventional CT, and that fewer patients were referred to ICA after PCD-CT, with those referred more likely to undergo revascularisation5. In this issue of EuroIntervention, Shin et al present a single-centre study examining 171 consecutive patients with prior coronary stent implantation who underwent CCTA with PCD-CT and subsequent ICA6. Only 3 stented lesions (1.1%) could not be reliably assessed for severity. Lesion-level sensitivity and specificity for detecting ≥50% in-stent restenosis (ISR) were 80.0% and 90.4%, respectively. Of note, in a subgroup analysis according to stent diameter (<3.0 mm [n=83] vs ≥3.0 mm [n=108]), no significant difference in overall diagnostic accuracy was found (92.8% vs 91.7%; p=1.00). Based on these findings and the initial clinical experience of experienced centres with CCTA, it is clear that PCD-CT represents a major advancement in the non-invasive assessment of stented patients, expanding the opportunity to detect ISR even in stented segments with diameters <3.0 mm, together with an improved accuracy in the evaluation of plaque burden and stenosis severity in non-stented segments. PCD-CT is still far from being a perfect non-invasive method to detect and characterise ISR. Shin et al reported an overall diagnostic accuracy of 88.9% for detecting obstructive ISR, but this result can be further improved because recent-generation CT scanners allow stress myocardial perfusion imaging to detect functionally significant lesions, with excellent accuracy compared with invasive physiology (fractional flow reserve and index of microcirculatory resistance)7. A unique advantage of direct coronary imaging with CCTA is that, unlike provocative tests (such as echocardiography, magnetic resonance or nuclear imaging) that can only detect ischaemia, CCTA also identifies the location and mechanism of ISR. The Mehran classification (edge, focal body, in-stent, proliferative or total occlusion), mainly based on angiography, has been largely substituted by the Shlofmitz-Waksman classification, based on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging, that adds information on the mechanism of ISR8. With PCD-CT, due to the high Z-axis spatial resolution (0.2 mm) − which is similar to ICA and comparable to IVUS, it is possible to differentiate neointimal hyperplasia from de novo lesions caused by disease progression. A possible residual limitation is the distinction of purely lipidic plaque from highly cellular neointimal proliferation, given their similar attenuation values. Incomplete expansion due to heavily calcified plaque around the implanted stent requires a very different treatment approach compared with severe intimal hyperplasia within a well-expanded stent, or to ISR due to a combined mechanism. In such scenarios, the interventionalist needs to first eliminate the cushion created by the hyperplastic tissue within the stent using cutting or scoring balloons to ensure the lithotripsy energy is effectively delivered to the outer calcium. With intracoronary imaging still far from being routinely used for ISR and the potential difficulties of advancing the probe in cases of very severe restenosis, PCD-CT can offer pretreatment measurements of vessel and lumen size, ISR length, and disease severity in adjacent native segments, i.e., all the information required for optimal procedural planning. The recent European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) consensus statement on the management strategies of heavily calcified coronary stenoses9 has proposed CCTA as an appropriate non-invasive tool for planning PCI in calcified lesions. CCTA is able to measure the extent, depth, and distribution of calcium, thus providing the same information that is entered into the IVUS/OCT scores used to determine the need for plaque modification techniques. The improved spatial resolution of PCD-CT might expand the usefulness of CCTA in this clinical setting to include stented lesions, enabling the differentiation of calcified neoatherosclerosis within a stent from a calcium shell around it. CCTA can also detect protruding stents at the ostium of the left main or right coronary artery and determine the optimal working view to avoid foreshortening of the restenotic segment; this is particularly useful in bifurcations and ostial restenosis10. The remaining challenge is the accessibility and understanding of this essential information for interventional cardiologists. Recent guidelines have provided a Class I indication for intracoronary imaging for guidance of complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). With fast-improving CCTA technology and new randomised trials testing it against intravascular imaging, it should not take long before an equally compelling recommendation is issued for preprocedural guidance with CCTA. Interventional cardiologists focused on coronary disease would do well to learn CCTA soon and master it sufficiently to perform the same accurate procedural planning for PCI that is now the standard of care before TAVI.

Figure 1. PCD-CT evaluation: high versus ultrahigh definition. Stent implanted in left anterior descending artery: (A) high-definition (resolution 0.4 mm) versus (B) ultrahigh-definition image (resolution 0.2 mm). Image courtesy of Prof. Francesco Secchi, University of Milan. HD: high definition; PCD-CT: photon-counting detector computed tomography; UHD: ultrahigh definition

Conflict of interest statement

C. Di Mario discloses institutional research contracts from Abbott, Amgen, Boston Scientific, Chiesi, Daiichi Sankyo, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Philips, and Shockwave Medical; and participation in advisory boards of Abiomed, Johnson & Johnson, and Terumo. D. Andreini has no conflicts of interest to declare.