Cory:

Unlock Your AI Assistant Now!

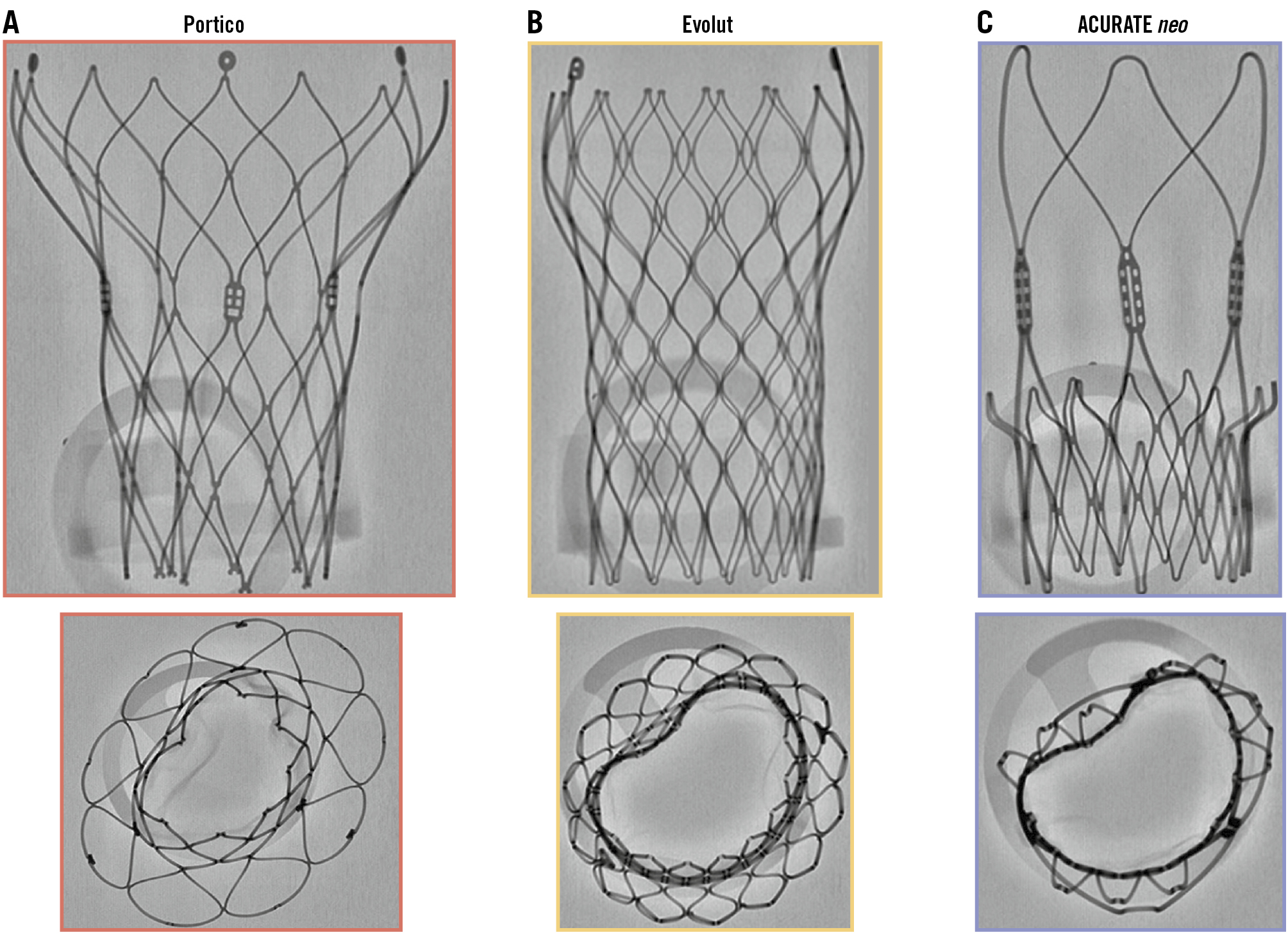

Traditionally, balloon post-dilatation following transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) was routinely performed to address paravalvular leak (PVL), clearly malexpanded valves with residual gradients, and occasionally, as a salvage manoeuvre for deeply implanted transcatheter heart valves (THV). The advent of computed tomographic sizing, external anti-PVL skirts, repositionable device technology, and increasing operator experience has more recently rendered routine post-dilatation less common: it is performed in approximately 20% of cases1, with lower rates for balloon-expandable valves (BEV)2. What are the potential drawbacks of post-dilatation? These include exposing the patient to an additional pacing run, increased procedural and fluoroscopic times, the cost of a balloon, and potential damage to the valve leaflets. Bench studies have shown that post-dilatation can leave an imprint of the THV frame on leaflet tissue, suggesting possible compromise of leaflet integrity3. The risk of THV embolisation, a disagreeable complication for both patient and operator, is often cited as a reason to avoid post-dilatation, especially with high implantation. And then, there are observational data that associate post-dilatation with higher rates of stroke and death45. These dated data are subject to selection bias and confounding, with patients receiving post-dilatation presenting higher-risk clinical and anatomical characteristics and suboptimal THV implantation45. Robust prospective data linking post-dilatation to adverse outcomes do not exist. What are the potential advantages of post-dilatation? It remains the only available tool to manage a suboptimal TAVI implant, short of implanting a second valve. Post-dilatation has the potential to reduce/obliterate PVL, improve haemodynamics, and correct frame malexpansion which usually occurs due to localised areas of resistant leaflet tissue or calcification. In 2017, in the pages of this journal, Fuchs et al were the first to associate regional malexpansion of self-expanding valves (SEV) with higher rates of hypoattenuated leaflet motion6. These authors also noted that malexpansion of the valve inflow usually implied malexpansion of the leaflet housing, a phenomenon that was reduced twofold among those receiving post-dilatation6. More recently, data from the ACURATE IDE trial have suggested an association between suboptimal SEV expansion and rehospitalisation, stroke and mortality7. While these findings are considered hypothesis-generating, they are nonetheless compelling and serve as an important reminder that an optimal implant technique is essential to ensuring longer-term clinical outcomes. In this issue of EuroIntervention, Husain et al publish the results of the DOUBLE-TAP study. In the aforementioned context, it is the first to investigate the impact of a routine nominal balloon post-dilatation after BEV implantation using both benchtop and clinical components8. On the bench, a 26 mm SAPIEN 3 Ultra (Edwards Lifesciences) deployed at nominal volume showed 87.2% midpoint expansion by micro-computed tomography (CT), a figure improved to 93.8% after a second “double-tap” inflation. The clinical arm, a prospective observational study of 102 BEV recipients, excluding patients with severe annular/subannular calcification or valve-in-valve procedures, has a primary efficacy endpoint of percentage THV expansion (midpoint diameter), averaged from 3-cusp and cusp-overlap views and compared to the valve’s nominal area. The primary safety endpoint was Valve Academic Research Consortium-3-adjudicated adverse events. Across all valve sizes, THV underexpansion was almost universally observed following initial deployment (range 70.2-81.0%) and a “double-tap” increased valve expansion by 8.6-9.9% (not significant in the 20 mm valve). At 30 days, no major complications were reported, and 9% required new pacemakers. While this study has limitations, including the use of two-dimensional fluoroscopic measurements to estimate valve dimensions and the underpowered nature of the analysis to detect haemodynamic or clinical outcome differences, the authors are to be congratulated for highlighting important issues that pertain to contemporary TAVI practice: an unexpectedly high prevalence of BEV malexpansion and the ability to correct this with post-dilatation. The absence of a short-term haemodynamic effect from post-dilatation should not be interpreted as evidence of a lack of longer-term consequences. THV malexpansion has been associated with leaflet pinwheeling, and bench studies demonstrate that BEV underexpansion of ≥2 mm (approximately 9% of the nominal diameter) results in leaflet distortion, increasing leaflet mechanical stress and ultimately compromising THV durability910. In the bench evaluations of the DOUBLE-TAP study, pinwheeling was reduced from 14.0% to 4.6% after post-dilatation8. Computed tomographic studies have previously reported malexpansion and frame deformation in >90% of BEV cases11, with the prevalence likely to be higher in more hostile and calcified anatomies. It is thus concerning that most patients in day-to-day clinical practice would potentially be at risk of early structural valve deterioration without post-dilatation of an otherwise appropriately implanted BEV. These results may be even more relevant to SEV technologies, especially those with intra-annular leaflets. Identification of THV malexpansion during TAVI is challenging, particularly since only one fluoroscopic view is routinely used for THV deployment and post-deployment assessment. Bench data demonstrate that even gross malexpansion can be easily missed unless multiple fluoroscopic angles are utilised (Figure 1). Indeed, in the ACURATE IDE trial, localised resistant areas of diseased native valve tissue were common (up to 20% of cases), often leading to significant eccentric valve underexpansion that was not readily identified using a single 3-cusp view. The DOUBLE-TAP study measured BEV dimensions in both 3-cusp and cusp-overlap views and identified malexpansion in >90% of cases. The authors report an additional 2-3 mm frame expansion with a second balloon inflation: can the naked eye detect this degree of malexpansion? The cusp-overlap view isolates the non-coronary cusp, where the most significant calcification is typically located12, provides a short-axis view of the aortic annulus, and typically allows a better assessment of THV expansion. Rotating the C-arm along the axis of the CT-derived S-curve can hence aid the identification of malexpansion, but understanding frame geometry in extreme cranial or caudal views is technically challenging. The good news is that malexpansion in the DOUBLE-TAP study was successfully managed with a nominal post-dilatation. An appropriately sized balloon yields a radial outward force of approximately 100 Newtons (N) to the surrounding tissue, while in contrast a SEV exerts a more modest 20-30 N outward force. In the context of BEV, the radial outward force is somewhere north of 100 N since it combines the effect of both balloon inflation and the circa 1.2 mm diameter of the metallic valve frame. Although not the subject of the DOUBLE-TAP study, these numbers illustrate why pre- and post-dilatation are so useful in SEV procedures, though it should be stressed that balloon forces are dependent on balloon type, size relative to the anatomy, and inflation force (2-8 atm). Where localised malexpansion exists due to resistant calcified leaflet tissue, the point force load in SEV drops as low as 6 N and will not be resolved unaided. If identified, this issue can be managed by post-dilatation with a return of the outward radial force of a SEV to a uniform >20 N. The mechanism by which a post-dilatation resolves the malexpansion observed in the DOUBLE-TAP study is unclear. There is typically a 5% recoil expected from the alloys used in BEV after inflation, similar to that observed with coronary stents. Post-dilatation may reduce frame recoil by further plastically deforming and strain-hardening the frame and by facilitating additional viscoelastic strain and expansion of the surrounding native aortic structures. An alternate mechanism of action may be that semicompliant balloons, such as those in the Edwards Lifesciences SAPIEN Ultra device, do not usually reach their nominal diameter on the first inflation. Additional expansion can be achieved at the same nominal pressure during a second inflation, a phenomenon consistently observed with semicompliant balloons. Ultimately, the DOUBLE-TAP study serves as an important reminder that oversimplification of TAVI with omission of pre- and/or post-dilatation may yield suboptimal longer-term results in a considerable proportion of our patients. We have been down this road before, in the setting of coronary artery disease, where direct stent implantation without optimisation was en vogue, and the adverse consequences of stent malexpansion became apparent over time13. Let us not make the same mistake again... Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. -Stephen King

Figure 1. Identification of frame malexpansion in self-expanding valves. Bench fluoroscopy of three self-expanding devices: (A) Portico (Abbott); (B) Evolut PRO (Medtronic); (C) ACURATE neo2 (Boston Scientific). The fluoroscopy demonstrates acceptable expansion in the frontal view (top) but clear frame malexpansion and deformation at the leaflet level on the axial view (bottom) due to the insertion of a fixture at the diseased leaflet level.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Chris Frawley, BEng for his input on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

D. Mylotte is a consultant for Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and MicroPort. B.W.T. Soh received conference attendance support from Bayer, unrelated to the present work.